The image above is from section 48 of Hammurabi's Code and it concerns the delay of payment of debt due to crop failure. The Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA) issued their own document concerning debt, around 3700 years after Hammurabi. A lot has changed in the intervening years, but not the government's interest in regulating debt and credit. This blog post is a part of a series that looks at that interest in the context of the cryptocurrency industry, with particular attention to the companies mentioned in the CSA's most recent guidance document: Voyager Digital, Celsius, BlockFi and Genesis. These companies, up until they went broke, managed billions of dollars of other people's money, and promised a new world of credit for crypto. What went wrong? What were they doing? Why have regulators taken such a strong interest? Read on to learn more about what was once a popular business model.

Borrowing From The Public: The BlockFi Business Model

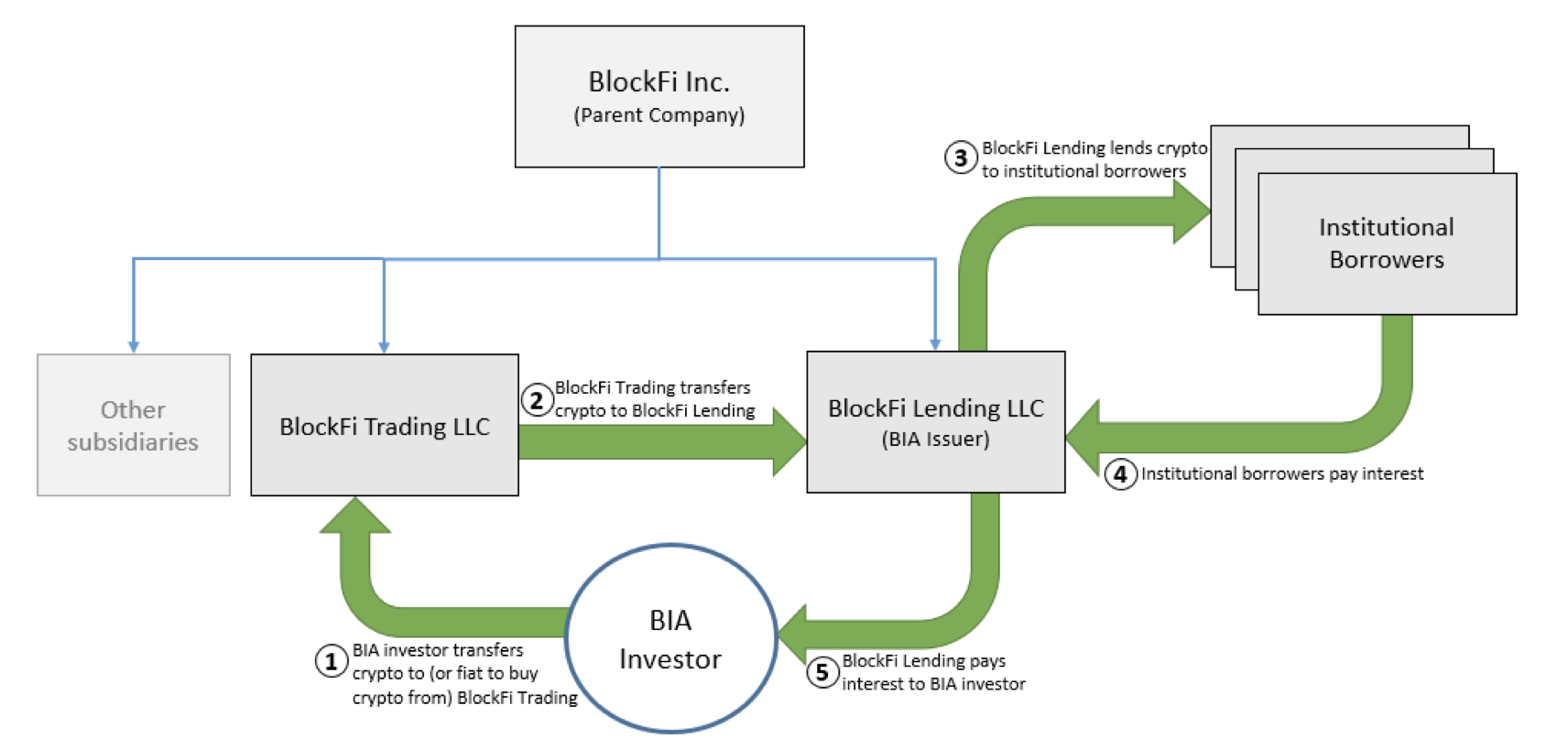

BlockFi settled with the SEC and 32 state regulators for a total of $100 million USD for offering a popular type of product: lending out crypto in exchange for a hefty interest rate (6.2% at launch, while banks offered ~0% at the time). BlockFi's product, according to the settlement, was launched in 2019 and paid the lenders in cryptocurrency on a monthly basis. BlockFi borrowed the money from anyone online, and used the money for its own purposes. The chart below, also from the settlement, shows the flow of funds in their system. In the chart, the "BIA Investor" is a member of the public who entered into the deal with BlockFi.

BlockFi told the investors that their money would be safe because the loans that BlockFi made (using their money) were over-collateralized

, but according to the settlement with the SEC: most institutional loans were not

. Apparently they hoped that the loans would be over-collateralized, but very few borrowers were interested in such a deal. The reason why not is obvious when the lending jargon is stripped away. An over-collateralized loan is one in which the borrower sends an amount of valuable property in excess of the value of the loan to the lender. But who would want such a deal? Very few companies have assets that can be easily sent out like that. Almost every borrower wants money because they don't have it, and in the crypto world, if you have the assets to provide as collateral, why wouldn't you just sell those assets? By 2020/2021, only a bit over 15% of the BlockFi loans were of this type, and the rest were under-collateralized or no-collateral loans.

Part of BlockFi's model involved a complicated type of investment fund in the United States for Bitcoin (Grayscale), lending to a (now bankrupt) hedge fund (3AC), and engaging in other types of risky lending. Essentially, the business model was to borrow from the public and then invest privately, and keep the difference between what it paid out to the public investors and brought in from the private investments.

Beyond the risk inherent in BlockFi's model, the model was also unlawful according to the legal analysis in the SEC settlement. The problem with the model was that borrowing from the public in the way they did created an investment contract. The facts are summarized on pages 8-9 of the SEC settlement:

BlockFi sold BIAs in exchange for the investment of money in the form of crypto assets. BlockFi pooled the BIA investors’ crypto assets, and used those assets for lending and investment activity that would generate returns for both BlockFi and BIA investors. The returns earned by each BIA investor were a function of the pooling of the loaned crypto assets, and the ways in which BlockFi deployed those loaned assets. In this way, each investor’s fortune was tied to the fortunes of the other investors. In addition, because BlockFi earned revenue for itself through its deployment of the loaned assets, the BIA investors’ fortunes were also linked to those of the promoter, i.e., BlockFi. Through its public statements, BlockFi created a reasonable expectation that BIA investors would earn profits derived from BlockFi’s efforts to manage the loaned crypto assets profitably enough to pay the stated interest rates to the investors. BlockFi had complete ownership and control over the borrowed crypto assets, and determined how much to hold, lend, and invest. BlockFi’s lending activities were at its own discretion, and BlockFi advertised that it managed the risks involved. Similarly, its investment activities were at its own discretion, and BlockFi could decide whether and how to invest the BIA assets in equities or futures.

Celsius and Voyager Digital

Celsius and Voyager Digital offered accounts that followed the same model as BlockFi. Each one had their own spin, but the essential model was the same.

The Celsius model was a bit more complicated, in that they preferentially paid interest in Celsius tokens (which they created), and state regulators in the US have alleged (but not proven) that Celsius was engaged in criminal activities, in addition to poor lending practices and possible legal violations related to lending. The founder of Celsius was sued at the start of this year by New York State on this basis. Other states have made their own allegations of fraud as part of the bankruptcy case, but these allegations are all as of yet unproven. The facts will come out in due time as these matters wend their way through the courts. Whether or not criminal actions took place, the approximately 600,000 user accounts of Celsius deposited around $4.2 billion USD of cryptocurrency that is currently caught up in bankruptcy proceedings.

Voyager Digital was a bit different from the other companies mentioned in the CSA staff notice in that they are a Canadian public company, but they didn't operate in Canada. The bankruptcy court in the United States that is handling their case recently put a stop to the sale of the company's assets to Binance, amidst claims by the CFTC (a US federal regulator) that Binance has broken many laws (read more about this in the lawsuit filed a couple weeks ago). The case against Binance by the CFTC has not been resolved and Binance disputes the allegations made against them (unsurprisingly, because they are very serious allegations, including violations of anti-money laundering laws).

Genesis And Gemini

Genesis, which has also gone bankrupt, was the most popular business-to-business lender that operated a similar model to BlockFi. Genesis filed for bankruptcy due largely to massive losses on loans to FTX (which is alleged, but not proven, to have been a multi-billion dollar fraud) and 3AC. Genesis reportedly lent $2.3 billion USD to 3AC. Signapore-based 3AC were also participating in the Grayscale trade (which turned against investors, who were previously making large profits), speculating in TerraUSD (which failed completely in 2022), and filed for bankruptcy in the summer of 2022.

The Genesis bankruptcy triggered a failure of another company offering a product similar to what was offered by BlockFi: Gemini. Gemini is most famous for being founded by Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss, who sued Mark Zuckerberg in 2004 for using his work for them on their social media concept and turning it into Facebook.

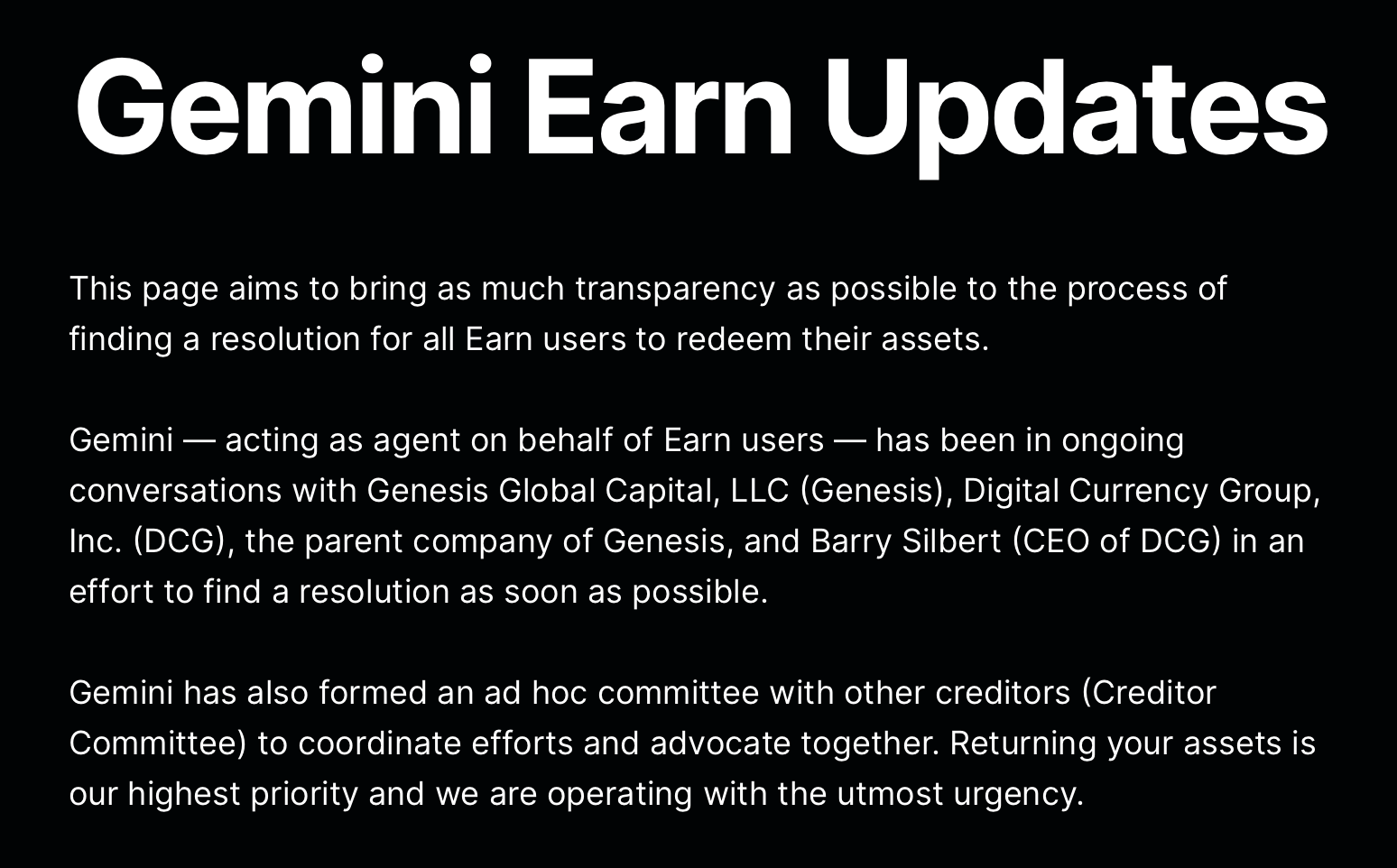

The public borrowing product offered by Gemini, called Gemini Earn

, is still paused. Gemini had a different legal model to BlockFi, but operated in a similar fashion to BlockFi and may be affected by the same regulatory issues that their competitors have faced, in addition to its credit losses from the collapse of Genesis.

Gemini and Genesis are involved in a PR and legal dispute over who is to blame and who owes what. These matters will become more clear as the dust settles and legal processes move forward. But in the meantime, there are nearly 350,000 people who are not able to access the cryptocurrency that they entrusted to Gemini, and they probably aren't too interested in the finer details about why. While that plays out, both companies were named as joint defendants in a 2023 SEC action that alleges that they sold securities unlawfully to the public (closely tracking the BlockFi litigation that led to the $100m settlement).

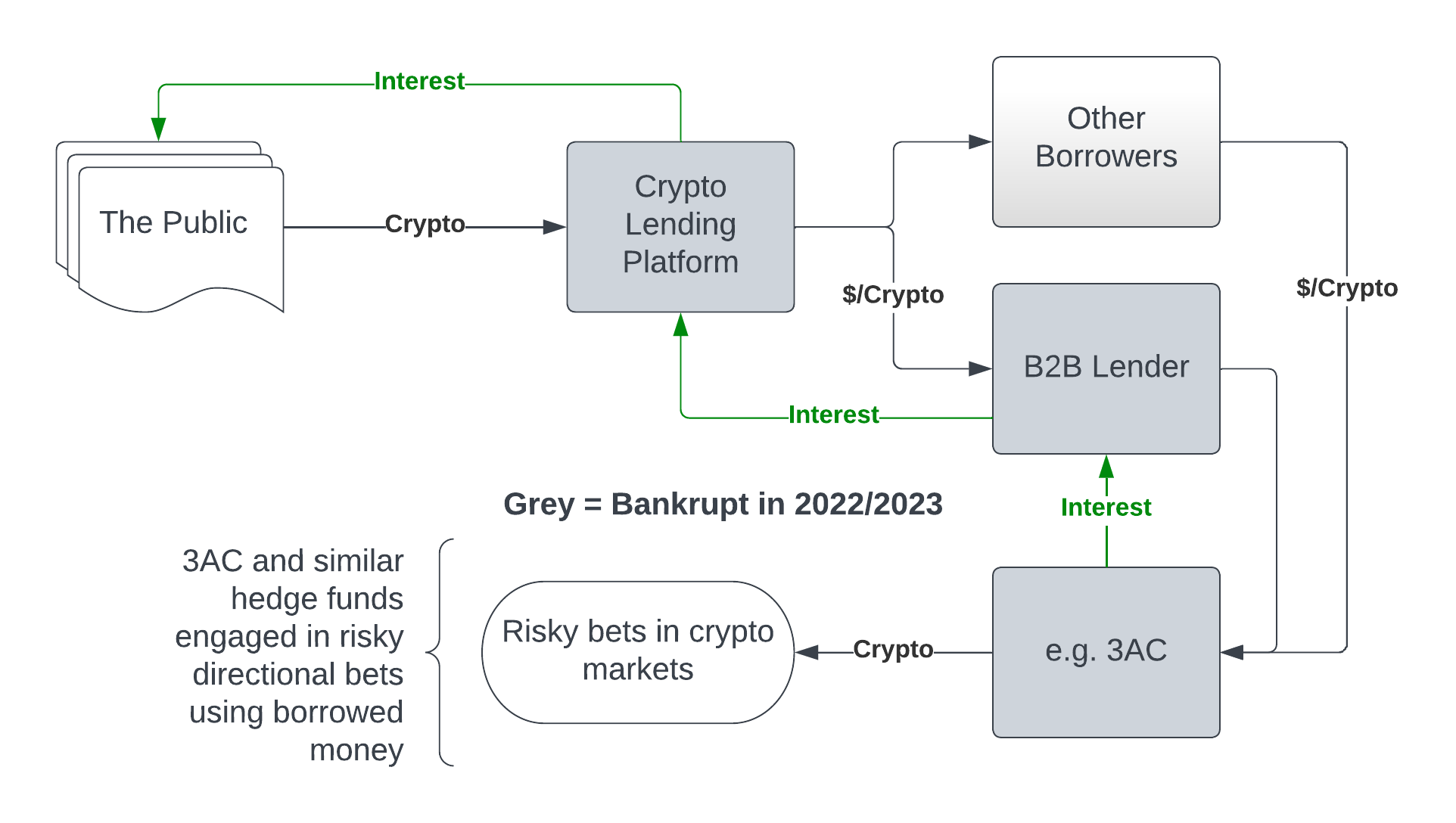

Close Relationships Between Companies

There were not that many players involved in the lending and borrowing businesses of the above-named companies. There was also a dependency relationship because the loans at different levels of the borrowing chain weren't independent. So the failure of 3AC cascaded upwards to the lenders who lent to them, and the lenders that lent to those lenders. A diagram of this flow is shown below (which is a greatly simplified version of complex, and disputed, borrowing activities).

Causes Of The Collapse

The various companies mentioned above have all suffered from the legal deficiencies of their models, but even if they didn't have any legal problems, they might have still gone bankrupt. The reason why is that they faced an almost perfect storm of losses all within a short period of time: crypto prices fell (damaging the ability of their borrowers to repay loans), frauds were uncovered, interest rates began to increase (making their products less attractive compared to regulated products in the banking/securities world), and TerraUSD collapsed. The collapse of TerraUSD (including its Luna token that was a part of the system) cost holders billions of dollars and its fugitive founder was recently arrested in Montenegro.

2022 was not a good year for the companies in the business of arbitraging the difference between what the public is willing to lend their cryptocurrency at, and what companies are willing to borrow at. The biggest risk to the business wasn't the change in rates (which most of these companies mitigated by having floating rates paid to the public), but the complete collapse of their counterparties. A bankrupt borrower can cost a lender up to 100% of their capital, and the cascading failures of companies that all suffer from the same weakness can bring down even the largest lenders. Even if there's a recovery in the bankrupcy process (which there will some degree of), the delay in being able to satisfy withdrawals of users means these products will probably not survive the 2022 stressors.

Things have come a long way since Hammurabi's Code, but the risks for borrowers and lenders are as real as they ever were. Whether its medieval banks in southern Europe, Hammurabi-era farmers defaulting on their loans due to crop failure, or Silicon Valley Bank - sometimes surprising events happen that cause bankruptcy. The public lost upwards of $10 billion+ on the failures of various interest-bearing schemes in the last year. Unsurprisingly, governments have been taking a close look, and they think that they can help avoid these problems from happening again. Read on to learn more about those efforts.

An Alternative View?

The above is almost entirely based on news reports and governmnt filings. The companies involved have their own narratives, and it's possible some of them will prevail in the various legal proceedings (while others have settled with regulators and foreclosed that possibility). Very little of this has been tested in courts, perhaps because the offered settlements were appealing to these embattled borrowers/lenders. There are actually intriguing legal arguments that these companies have made, and might make. Loans are surprisingly not as open and shut of a case as one might think, and the next blog post in this series will discuss that a bit.

Next Post: How Loans Are Regulated, Then: The CSA Staff Notice

The next post in this series will look at how loans are typically regulated in Canada (and similar countries). The next post after that will look at the CSA staff notice, in its full context of crypto lending, and also at decentralized alternatives to these centralized lending operations that may be the future of crypto-related lending.