We need a new system of law publishing in Canada: Digital Law

. Digital Law is a change in the way laws are made available to the public, not a change in the structure of our legal system or the entities that create the law.

This is the second in a series of posts about solving the A2J crisis

. The first article explains the larger problem and provides context for this piece.

I've begun with the solution (Digital Law), and assume that you believe that Canadian law is effectively unavailable to the public in 2019. If that sounds wrong to you, or you're not familiar with the details of the legal system & legal publishing, you may want to start with the problem statement at the end of this article.

Canadian law is not available to the public and that's the first problem that needs to be solved before the public can access affordable legal services delivered through digital platforms (the only way to achieve low-cost law at scale). This post explains what's not published online, what should be published, how it should be published, and why Digital Law is the first step towards solving the A2J crisis.

The Solution: Digital Law for a Digital World

Wherever you live in Canada, your life is governed by millions of legal rules encoded in a variety of documents that set out what the law is. It's impossible for anyone to read a tiny fraction of these rules, even if they were published (and they often aren't). There are so many laws that the only possible hope of people being able to follow the law is if it's encoded digitally and available to people digitally. No country does this yet but Canada could do it in a matter of a few years, at relatively low cost.

The Digital Law Future: Proposal for a Modern Legal System

Here are the features of a new Digital Law system:

A. All law published online, in a standard technical format

B. References within laws published in a standard technical format, or a standard human format (e.g. McGill Guide)

C. Standard API to access the law (e.g. US Federal Register API)

D. Municipal laws registered and published along with provincial laws

E. Plain English summaries of the key elements of the law (e.g. NSCA headnotes)

F. Presumption of openness and free access

Below are explanations of the above features and why they're important.

First Step: Publishing Everything

The first step to Digital Law is to publish everything that's intended to be a part of the law. That's not the case right now and Canadians are being left in the dark about what the law that governs their life is. This needs to change and law must be made available to the public online. The next step is to make what's published useful, but if the laws aren't published comprehensively then everything else is moot.

Standard Technical Format

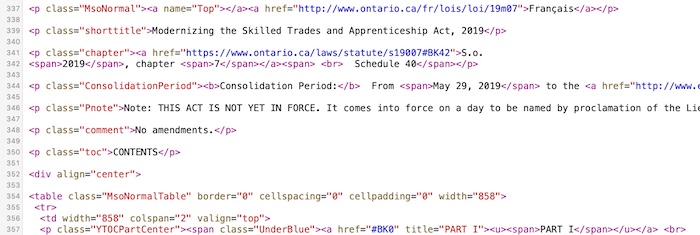

Laws are data. Right now that data isn't structured in a way that computers can understand. The data needs to be formatted consistently and properly.

In the same way that people must fill in the forms correctly in order to get services from the government, the government needs to fill in the "forms" for us about what the laws are. Laws must be in a format that can be read by computers and people.

Why Format Matters

A common saying in computer programming is garbage in, garbage out

. Our legal system suffers from a garbage in problem. This problem is created by the wide variety of organizations entrusted to create law (who don't work with each other) and a lack of knowledge about why or how this should be done. The legal system continues to publish its output as it always has, even while tech companies invest billions into Big Data and data [is] the oil of the digital era

.

Making Law More Accessible

An important benefit of providing standardized formats for law is that they can be translated using automatic translation tools for non-native speakers. Machine translation has advanced to the point that translations can be done accurately and quickly, and this can help Canada deliver on the promise of a bilingual country, while also providing access to the millions of Canadians who can't read French or English fluently. This would be impractical to do with human translators, but can be done efficiently at scale for dozens of languages with good quality results due to recent advances in the field. Standard formats are the first step towards unlocking laws using other types of technologies, whether that's automated translation or screen readers

for people with sensory disabilities.

References Are Essential

How laws relate to each other is a critical feature of our legal system. Judges interpret laws and elaborate on the laws, and they do that with reference to existing laws. Those references must be standardized in order to allow computers to understand relationships between laws. The relationships and references between laws are often a critical element of the legal rules because of the interdependencies that exist in Canadian law (e.g. the Ontario Interpretation Act).

It doesn't matter what the format is, it just needs to be consistent.

APIs Are How Computers Talk to Each Other

APIs are standard interfaces for computers to access data. Most laws today are published in ways that humans can understand but don't provide any programmatic way to access laws. The best example of what this could look like is the United States Federal Register API. Although there have been some efforts in Canada like the BCLaws API, APIs are not typically available for Canadian law. This needs to change.

APIs are subtly different than standardized law. The APIs are how computer programs can access the systems that hold the laws.

Municipal Laws (+ Everything Else)

Municipal laws are important but rarely available to the public. The City of Toronto published well over 1000 by-laws last year and there are millions of by-laws across Canada that can't be searched or discovered without making a trip to a research library. These laws should be registered in a central location and made available.

The broader point is that all laws need to be made available to the public, no matter what form they take. There's a lot more to law than just provincial or federal statutes and regulations.

Plain English Summaries

Most laws are written in legalese

that can't be understood by the public. Where possible, the people making the law should write a summary of it, organized by what's important to the readers. A good example of this is the format of Nova Scotia Court of Appeal decisions (e.g. this recent murder case). Although computers can summarize information, today's technology isn't capable of providing the sorts of concise summaries that legally-trained people who work with the subject matter frequently can produce.

Presumption of Openness

The key to Digital Law is a presumption that laws are open to all and ought to be made available. This concept is resisted by many participants in the legal system, in part because they're comfortable with the status quo and don't see what advantages openness would have. Yet this is at odds with how most Canadians view the legal system, and I think most people would be surprised to find out that there are barriers to accessing the law. The Canadian Judicial Council (the organization for Canadian judges) has this to say about allowing the public to find case law (Model Policy for Access to Court Records in Canada, s. 4.6.1):

However, if the judgments are posted on the internet, it is a good practice to prevent indexing and cache storage from web robots or 'spiders'. Such indexation and cache storage of court information makes this information available even when the purpose of the search is not to find court records, as any judgment could be found unintentionally using popular search engines like Google or Yahoo.

The above quote is at odds with the growing movement for open data in Canada and abroad

, where governments have recognized that open data is important. All of the above points about Digital Law can be mapped to Canada's Open Data Principles, and similar statements about Open Data published by provincial governments and municipalities. The time is right for adopting Digital Law, and a very strong presumption of openness.

How Much Would Digital Law Cost?

Digital Law would likely end up being cheaper than the current system of ad-hoc publishing where thousands of different organizations are expected to figure out how to make their legal documents available. A standard system would streamline this and greatly reduce the IT costs involved in maintaining these systems.

A relatively modest team of people could support the entire country's infrastructure for laws. Modern software delivery methods allow very small teams of developers to deliver hugely impactful systems.

Even if Digital Law wasn't cheaper than the current system, the consumer advantages would be so enormous that I can't imagine a cost-benefit study wouldn't conclude this to be a more cost-effective approach. The current model relies heavily on non-government actors supplying the appropriate metadata and formats as to make the law useful, but this comes at a heavy cost in the form of legal product subscriptions and inconvenience for the public.

How Does This Help?

Digital Law is a necessity in our digital world because it enables every other type of digital solution. Laws today are simply too numerous and too important to work with on a manual basis. We need to upgrade our infrastructure in order to start delivering cheaper legal services to the people who need it (which is all of us). If we don't have Digital Law then we can't have affordable, good quality digital legal solutions. Digital Law is an important first step toward solving the A2J crisis.

The Problem: Canadian Law Isn't Available to the Public

Most people have a hard time believing that law isn't available to the public. But as someone's who has practised law for many years and developed several businesses based around making legal information available, I have first-hand experience with this problem. Law is often theoretically available, but not practically available (or even actually available). The ways in which the law is made not available are a combination of a lack of attention, lack of investment, commercial relationships between government and publishers, and sometimes, an interest in concealing the law.

Canadian law is a combination of laws published by the government, court cases distributed by the court system, and various kinds of legal documents issued by boards, tribunals, and other arms of our sprawling bureaucratic state (for example, Ontario alone has 191 provincial agencies). It shouldn't come as a surprise that when lawmaking is divided amongst thousands of different participants, not all of them do a good job of making their work product available.

Much of the law isn't published online, and where it is published online, it's sometimes restricted by contract so that it can't be used to develop tools to help the public. And even when it is published online, the data is not properly formatted.

An example of law not being made available is the Ontario Superior Court of Justice. On the webpage for how to obtain a court judgement:

Once a judgment has been issued in your case, you may obtain a copy of the judgment from your lawyer or from the court office.

A photocopy fee will apply if you wish to make a copy of the judgment from the court file. You may also obtain a copy of a judgment in a case to which you were not a party upon payment of the prescribed fee.

Currently, the Ministry has no central database where current and past cases can be accessed. Certain judgments from all levels of court in Ontario are available online through the Canadian Legal Information Institute. Most Ontario Court of Appeal decisions are available online at the Ontario Court of Appeal website.

Certain judgments can also be obtained by accessing a retail legal software database. You may wish to consult a librarian at a law library to find out more information about companies, which provide such software and services.

Laws Are Messy: Dealing with Unstructured Data

Canadian law is not available to the public online. That's the first problem that needs to be solved before the public can access affordable legal services. If the laws aren't available to be read, how can people be expected to follow them?

Canadian law is published in thousands of unstructured formats by courts, agencies, boards, ministries, and governments, without any standardization. Many boards simply don't publish cases at all. For example, the Ontario Highway Transport Board (which regulates bus services in Ontario) doesn't publish any decisions online, and doesn't list anywhere on their website where people could obtain decisions. Even the Ontario Superior Court doesn't make all of their decisions available online, and outsources publishing to an organization funded by the Federation of Law Societies of Canada, which then bans automated collection of the cases through their terms of use agreement (in part required by upstream licesors, the courts & boards) and technical countermeasures.

How Lawyers Access Laws

Lawyers primarily access law through subscription services like Westlaw, textbooks, and other services that aggregate legal information and publish it in formats that can be used.

In Ontario there are two major commercial services that ingest the law, in part through secret deals with the court system, and then pay people to clean up the inputs and format the data in structured ways. This is a multi-billion business globally. The #2 legal publisher in the United States, RELX Group (familiar to lawyers as LexisNexis), makes over $2 billion/yr globally on formatting & distributing legal information generated by the legal systems of countries like Canada. Although there are some small players like vLex making inroads in the market, there's a limit to what can be done at an economic cost in the current environment.

Other Countries Aren't Better

As part of developing the world's most comprehensive foreign law legal search engine, I wrote hundreds of computer programs to access the laws from legal portals around the world. There may not be anyone in the world who has looked at more law publishing formats, and written code to extract legal data from them, than I have. No country has solved this problem and all of them suffer from a lack of attention to the means by which laws are made available to the public. Lawmakers consider it their job to make laws, not to disseminate them in a format that can be used by the public (let alone computers).

Access to Justice Through Digital Law

Digital Law is law that can be understood by people. Not directly, but through the tools that people will inevitably build around the law. Today this is a multi-billion business for companies like Westlaw and LexisNexis, and could be even bigger business in the future. But Digital Law isn't a proposal to help big legal software companies. The type of businesses that could be built around Digital Law are fundamentally different than the current structure in which a small number of companies dominate the industry through private deals to gain access to court decisions. Free, public, standardized data is the raw material needed for creating legal products to serve Canadians.

If Digital Law became the standard in Canada then incubators like the Legal Innovation Zone could quickly cultivate a wide range of tools for Canadians. Some of the ecosystem already exists to take advantage of Digital Law, but the government must do its part. Private actors can't force boards to make their decisions available online.

Fortunately, governments of all levels now recognize that there's value in making data open. The Government of Canada has this to say about Open Data:

The Government of Canada believes it is important to provide Canadians with access to the data that is produced, collected, and used by departments and agencies across the federal government. It is equally important that the data is made available through a single and searchable window. We have consolidated data from across government departments and agencies and have provided access to them all in one place.

Why not for law?