There are three assumptions widely held by the public, lawmakers, and even many lawyers. The three assumptions are, together, the FEF assumptions, which is that laws are:

1. Followed

2. Enforced

3. Free

1.Followed

Many people view laws as a moral imperative. They may even believe that the role of the legislature is to enshrine morality in the form of laws. Something more like a guidebook than a mandated rule backed up by police and prisons. Your world view may be somewhere between those poles, or off in another direction. But there's generally an assumption that the law will be followed by the citizenry.

It is of course quite untrue that people always follow the law. Criminal courts are quite busy. But even in civil matters, people regularly experience corporate or government action that is off-side of the law. Despite abundant evidence to the contrary, there's a strong assumption that passing a law will make it so.

2. Enforced

When laws aren't followed, it is expected that punishment will follow. People have a strong believe that what is law is also enforced. But people on the receiving end of the myriad laws of the modern state know that laws are only selectively enforced. Some laws aren't enforced at all. It's a frequent question that lawyers get due to the huge number of laws. Of course, ethical rules mandate that lawyers tell their clients to always follow the law. But lawyers and clients alike know that laws differ greatly in terms of enforcement, partly based on political will. The dollars available for enforcement activities are often quite slim. In some parts of the government, there may be only a handful or sometimes no staff available to go out into the world anc check up on whether laws are being followed.

3. Free

The clever reader might scoff at the third assumption in particular. Even the government publishes "cost-benefit analyses" of laws. But it's never the case that the analysis produces a negative answer! Not once have I seen a (mandatory) regulatory impact assessment that concluded the costs would exceed the benefits. In the (many) analyses that conclude that the financial costs are very high and the financial benefits are very low, the authors simply assert that there are many other benefits which greatly outvalue the costs. This is the free part.

Laws aren't free but they're treated as such by the people who propose them or just generally support making more laws (like virtually all lawyers, and surprisingly, not for the self-interested reason of more laws = more work). But people are easily swayed by the idea of the benefits and have a hard time guessing at the costs, or don't believe the costs will be important. They believe that the law will be free

in that there will be an enormous net benefit - a free gift to society at large.

Academics, and economists (the math side of politics) in particular, often don't believe in a free lunch. They believe, and there's an enormous literature on the subject, that laws often have unforeseen costs. And that's without considering the costs of the taxes that are often required to carry out a law.

Why Are These Assumptions Making Life Hard For Honest People?

Wrong assumptions about laws have led to enormous support for increasing the numbers of laws. And the growth of law has followed.

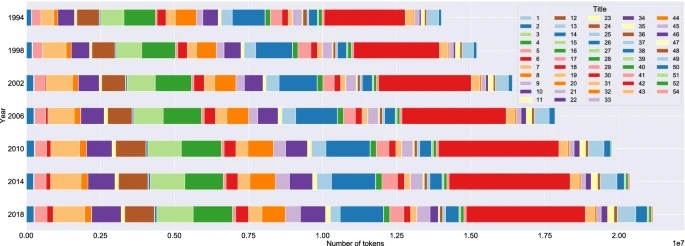

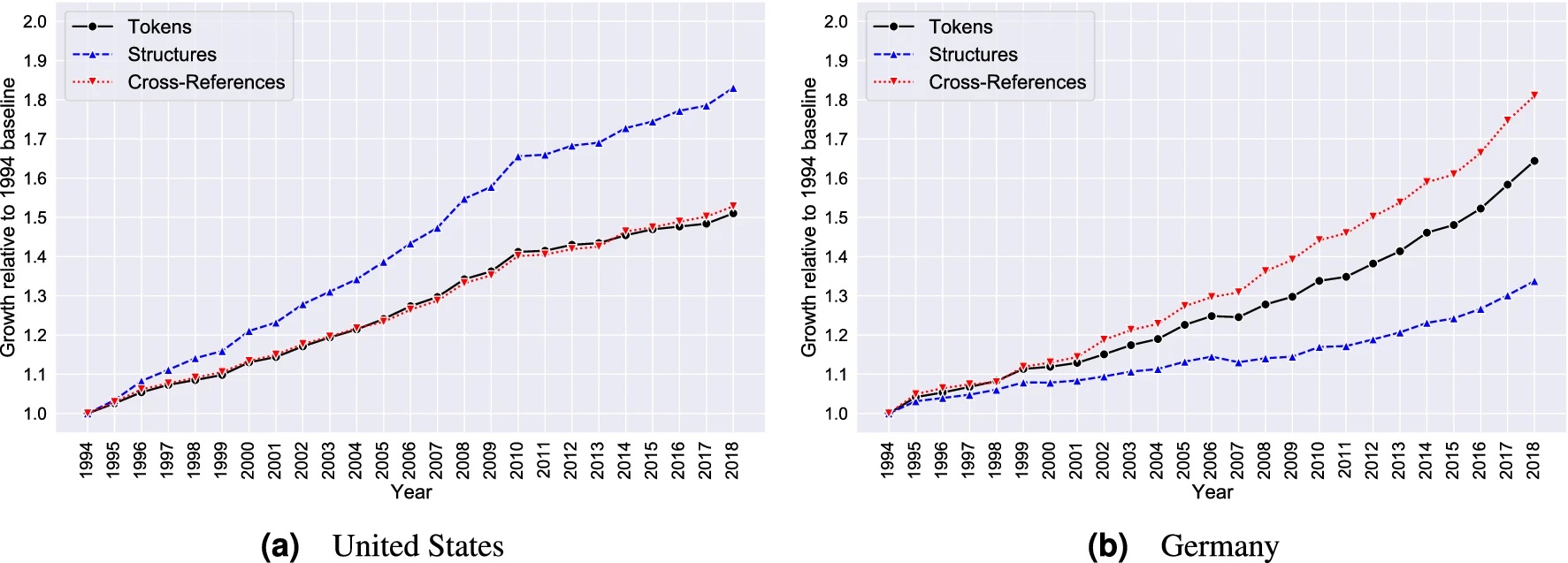

The explosion of laws since the 1990s is evident from the graph at the top of this blog post, which graphs US federal law. This is not just a US phenomenon. Below is a graph that shows the growth of laws in Germany and the United States. These graphs are both from a 2020 paper in Nature titled Complex societies and the growth of the law

. In both Germany and the US the quantity of federal (not even state!) legislation expanded by 50-75% (depending on how its measured). Canada has also seen a large increase in law but with less scholarly attention.

So what? Who cares if there's more law? The answer is probably not many people, but that's because most people can't understand the laws and make the FEF assumptions. Many lawmakers don't even read the laws they pass because they're too long. The public has no chance! And that's before getting to the FEF assumptions.

The FEF assumptions are not good ones. Laws have consequences and costs. And the great expansion of law in the last few decades has led to a huge regulatory burden, and underenforced laws throughout modern countries. When laws go unenforced people lose respect for the law. And perhaps more importantly, people are discouraged.

Honest people are discouraged by a large number of legal obligations. Dishonest people don't care. They don't plan on following the law, and in fact it can be an opportunity. Environmental laws are a great example of this - they're hardly enforced at all and pollution abounds. But even at a more mundane level like running a restaurant or even starting a law practice, a large number of legal rules discourages people from even trying to comply if they're honest. This causes consolidation of industries and a reduction in entrepreneurship.

Is It Really True That Entrepreneurship Has Declined?

Official statistics shown hardly any change in the percentage of self-employed people in Canada since the 1990s, so that would seem to indicate that entrepreneurship has not been impacted by the increase in laws. But this may be a paradoxical effect because laws can push companies (and the government) to convert people to self-employed contractors rather than stay as employees. This effect may hide the reduction of self-employment over time. It may also reflect rising income taxes causing a shift in the structuring of work. These numbers are very hard to use to tell a clear story.

Impacts Of More Laws

A different way of viewing the impact of laws is on rising concentration of many markets. Throughout North America there's been consolidation and a reduction in the number of competing firms, for a variety of reasons, but surely the increased burden of complying with laws is one of them.

My personal experience with young lawyers/law students is that they are very concerned about the number of rules that they'll have to follow out of the gate. Having a lot of rules means that people who are new to the business will have a hard time, whereas the incremental cost of a new rule for long-standing businesses is less.

A famous economics paper from 1971 by George Stigler made the case that over time regulatory apparatus eventually come to serve the needs of the regulated, and not the public. Debates over the veracity of this consume many scholars' careers. Although certainly not the whole story, it's certainly true that companies view laws as a moat

and try to strengthen the moat where they can. It's a key reason why companies call for regulation

. There are investors who have even made their career on investing in regulated industries, such as Warren Buffet.

Back To The Honest People

Stories about insurance companies monopolize markets make people annoyed (or at least, make them pay more) but tend not to change many minds. The FEF assumptions are strong in the minds of the public. But it would be helpful for more people to question these premises and consider whether doubling the quantity of laws every 25 years is a sustainable path. Even for people who love the idea of having more laws, they should ask whether lawmakers are delivering what they really want.

Most people want followed, enforced, and free laws. What they get is often evasion of laws, lack of enforcement, and burdensome costs. Laws vary enormously in efficacy, enforceability, and cost-benefit analysis. But politicians propose all laws as if they are alike. The news reports what they say, and when they don't, they may pick partisan commentators or make superficial remarks. The truth about laws is that they're very complicated and often have impacts that are not obvious. They're rarely free, and even when they have great benefits, the costs may be borne by some groups far more than others.

None of this is particularly novel commentary, but that's why it's all the more important for people to recognize the assumptions they're making when suggesting that such-and-such activity become regulated

. Is the future of Canada that every activity will be regulated? Will utopia really be achieved when a license is required for every activity? Law clients of mine often assume there's a license for everything and they want one. Increasingly, it's actually true! But it's probably not the best direction to go as a society. Having simpler, general rules of conduct, and having a smaller number of properly enforced laws was once a consensus view in Canada and elsewhere. In the world of rapidly expanding law, there's nothing wrong with asking more questions and challenging the assumptions behind expansion of law. If people don't then they may find that honest people are pushed out in favour of those who fail to abide by unenforced laws. Or perhaps an even worse outcome: strongly enforced laws against everything!

What Laws Ought To Exist?

Everyone has a different opinion on what laws should exist. There's no way yet invented to know the optimum quantity and character of law. But the more people challenge assumptions and carefully consider legislative proposals, whether at the level of lawmakers or the public considering what politicians or regulators are promising, the more likely it is that people will like the future that they help to create. Since laws are rarely revoked in modern states, the laws that are determined now will flow down to the people of tomorrow, potentially for centuries. This is a great burden and one that should probably be carried with greater thoughtfulness.

What's This Post Really About?

Calls (by many people, companies, and lawmakers) for (unspecified) (more) regulation in the realm of the global technology industry, of which cryptocurrency is a part.