A few weeks ago, the C.D. Howe Institute in Toronto wrote a commentary on stablecoins created by central banks, specifically the Bank of Canada: https://www.cdhowe.org/public-policy-research/two-sides-same-coin-why-stablecoins-and-central-bank-digital-currency-have. The report is called Two Sides of the Same Coin: Why Stablecoins and a Central Bank Digital Currency Have a Future Together

. This commentary is a great opportunity to explore differences in opinion on this issue because C.D. Howe's works is quite good, and independent.

One of the authors of the commentary, Mark Zelmer, is the former Deputy Superintendent of OSFI. The excellence of the authors is a great reason to look at this report critically. The commentary contains a number of premises that are worth challenging, and conclusions that are far less definite than the commentary makes them out to be. This has implications for governments, like Canada's, that are trying to grapple with modernizing their money systems during the "Great Digitization" (i.e. now). It also has profound implications for Canadians, who may soon be using a new type of money.

A Disclaimer

I work for companies that work with stablecoins. This blog post does not reflect any of my clients' views and none of them were consulted on it (like all of my blog posts). Personally, I want Canadians to have the best services available, and to become world leaders so everyone can prosper - whether that means government, private, or a hybrid.

Cash Is Risk-Free?

It's commonly said in finance that cash is "risk-free" but this is only true when measured in the currency of interest. For people who hold Turkish Lira, cash is extremely risky, having devalued more than 90% in the last 15 years. Canadians too have been suffering from inflation, most recently due to the federal government's response to Covid (re: politically-induced money printing that decreases the value of the money in circulation).

Inflation is running around 1.8-4.7% according to the Bank of Canada (they publish several numbers that are "inflation"). Reported inflation in the United States is even higher. And if inflation is measured from the perspective of young people, the things they want to buy (like houses and food) have been rapidly increasing in price. Whatever the true measure of how much less a dollar is worth this year than last, the Canadian Dollar is not a risk-free asset as measured by purchasing power (which is really the only logical measure since that's what regular people want dollars for).

For most people, holding cash is risky in that there's a near certainty it will be worth considerably less at the end of each year. The trope of "risk-free" cash, in the sense that regular people understand it, is one that should probably be retired. Just because there's no loss denominated in Canadian Dollars, that doesn't mean it didn't occur. The footnote in the C.D. Howe commentary notes that people can lose due to counterfeiting and theft, but surely inflation is a more significant source of loss for Canadians. Worse, it's by design. The Bank of Canada recently reaffirmed their commitment to dollars becoming devalued over time. That's not a great way to get the rest of the world using our money, and if other countries don't want it then Canadians probably aren't really making a positive choice to use CAD.

Inflation Is Not An Unalloyed Good

It's important to know where losses are occurring so that people who don't want to lose can make choices to avert the loss. It's easy to imagine someone preferring a type of money that doesn't have high inflation, or that doesn't have the risk of money-printing inflation. Introducing a government-backed stablecoin does not solve this problem.

In a world where stablecoins like this become more popular, it's entirely possible that Canadians might choose to move their money to currencies that don't have this issue, and the pursuit of a government stablecoin could actually accelerate this trend.

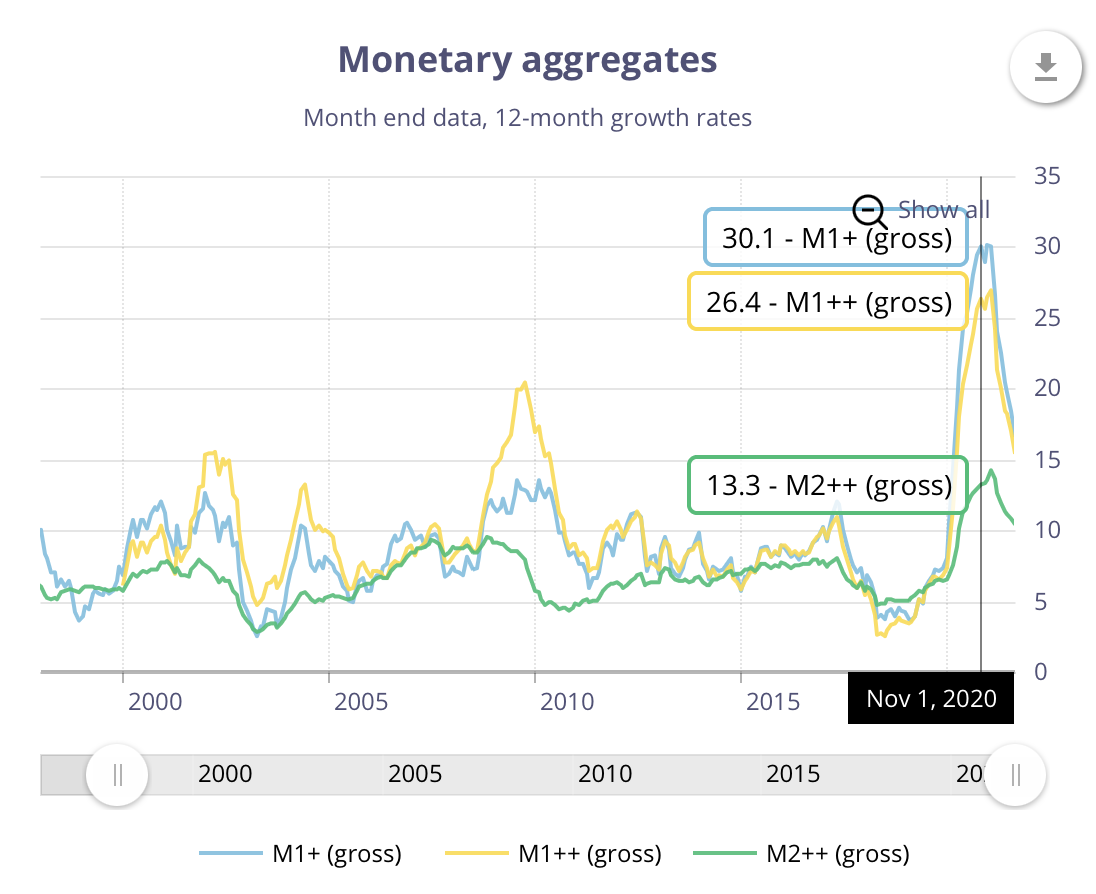

The C.D. Howe commentary doesn't consider whether people might want to not have inflationary reduction of the value of their dollars, and instead suggests that governments need to be able to do this in an "emergency" and to "stablize the economy" (pg. 3). But imagine a person who takes no part in the credit system, and what they would want: a stable dollar. They don't want a dollar that can suddenly change in value in order to give money to politically-relevant entities like banks and securities dealers (re: Great Financial Crisis). It is far from obvious that this is the only way to stablize an economy, and ignores the cost to the people who hold the money. Last year, the money supply was growing at 12-59% per year for a while (depending on the Bank of Canada statistic used). It is not obvious that this is good for the people who hold cash, because they suffer a direct financial loss of purchasing power, while other people gain access to the newly created dollars (and without any discussion or law being passed, since the Bank of Canada is officially independent from Parliament). The losses from inflation, on the ~$3.1 trillion of Canadian Dollars (M3, gross, unadjusted) at 5% per year is around $150 billion per year. Inflation is not "free money", and it's highly debated by economists.

Related: at the beginning of this year I wrote a blog post on the future of MCMA (multi-currency, multi-asset) wallets, and whether that's where we're headed.

An Assumption About Banking & Payments: That Technology Is What Banks Lack

Like many people, the authors assume that banks and payment systems can't do what Bitcoin does. I'm not sure this is correct, even after years of working in the emerging cryptocurrency industry.

Banks, and the payment systems they run/use, could theoretically do a lot of what Bitcoin does, and do a lot more. But they don't want to, and often can't. There's an element of consumer demand to this, but much more important is the role of regulation. Laws stop this from happening. Our laws ossify existing structures and force companies to act as they did before, in order to fit within the box provided for by law. It doesn't seem like a primarily technical issue to me. APIs are being used by everyone in the crypto industry anyway, because despite the rhetoric about decentralization, much of the crypto ecosystem is based on the same Internet-based approaches used for other services.

Old Business Models Aren't Being Copied And Pasted

Another assumption the article makes is that companies in the DeFi space are looking to monetize data flows. The authors write: "The crypto firms are seeking to profit by exploiting the information contained in the transactions flowing through their platforms." Generally that's not happening, in part because the data is actually open to everyone. There's also very little metadata that can be exploited.

DeFi is an example of customer-first technology, rather than companies looking at this and trying to figure out how to run schemes against their customers (re: Robinhood + Citadel with PFOF). Many people naively assume that the crypto industry is repeating the same practices as traditional financial intermediaries, but this is usually not the case.

Typically, DeFi businesses are running very low margin services that rely on big numbers because they serve a global market. When you have 100x more customers, you can charge 20x less and still make 5x more money.

Ascribing Motive To A Neutral, Open-Source P2P Network

The authors use a colourful expression that might mislead some readers who are used to companies and governments having long-term plans, and secret motivations: "It is a cryptocurrency that aspires to be a widespread medium of exchange." Bitcoin does not aspire to anything. That's one of the more interesting things about it. It's an idea, it's a protocol, and it's a variety of different clients for the P2P network.

To the degree that there's any uniform opinion of the developers who work on cryptocurrency, it's usually to make it the best it can be, and then see what happens. This is a refreshing difference from central bank currencies that don't share this focus on the end user. The C.D. Howe report has a major focus on convenience for government, and opportunities for intervening in markets, but that's not something many individuals clamour for.

I've never seen a protest calling for injection of liquidity into banks that are experiencing temporarily low margins on their credit products. It's important to ask: who is this for? Who benefits? Banks? The federal government? Regular Canadians? Any technology that is most focused on the latter is probably going to be the one most people want, but due to political power, other constituencies end up with the seat at the table.

Disrupting Credit Markets

On page 7, the authors raise a concern that private stablecoins, like Facebook's, might "potentially [disrupt] traditional credit allocation". But wouldn't that be a good thing? The financial sector in Canada is an enormous cost borne by other sectors of the economy. To the degree that any technology disrupts credit allocation we should probably be thankful, because it would only succeed if it's truly popular. Unlike a government-backed money system, the private versions and the software that interacts with them can only survive by convincing people to use them. If more people choose them, and traditional credit players suffer, this likely means that the economy is improving in efficency.

The authors might not dispute the above, because they add at the end that the real problem is that this might impact the ability of the Bank of Canada to carry out "monetary policy". In Canada, this means primarily a deliberate introduction of inflation, which erodes purchasing power, at a rate of 1-3% per year (according to the Bank of Canada). But which is it? Protecting existing credit markets, or protecting the ability to cause inflation? And if inflation is so great for the people experiencing it, why don't more people flock to the Canadian Dollar? In reality, the Canadian Dollar is very unpopular worldwide, being used in hardly any places other than Canada (i.e. places where Canadian tourists flock to).

Is Cash Always Nefarious?

The authors, on page 7, mention that $107 billion dollars in bank notes were printed by the Bank of Canada in December of 2020. They ask why there's so much cash being used, and what it's used for. They conclude:

... two possibilities: either their use is for illegal or nefarious activities or, in this exceptionally low interest rate environment, they serve as a store of value for savings purposes without much loss of interest income.

They omit a third possibility: the use of cash for its intended purpose. Cash is not just used for crime or saving money. Cash is also used widely for payments in Canada, and it's quite efficient for some kinds of transactions. It's also quite private, which is something worth considering in a world where the impacts of the loss of privacy are starting to be felt in terms of reduction in freedom of speech, stalking, the unbanked, and a myriad of other impacts on the citizenry.

The perception that cash is only involved with crime is fairly widely held, but obviously false, and in any event, cash is issued directly by the government. Nothing can be more legitimate than using bank notes in Canada, and it's actually the only thing that qualifies as "legal tender" (along with coins from the Mint). Not everyone wants Mastercard and VISA to follow them around, and people's political views about money shouldn't be taken lightly given the central importance of money to our lives.

An Unreasonable Belief In Regulation As The Source Of Goodness

It's common for people to believe that because there's a law, the law is the cause of all the good things that have hapepened. Or that because there's a regulator, the regulator is responsible for the good outcomes. It's a nice belief to hold because it's difficult to falsify, but in many cases, it is obviously not correct. I suspect the authors of the commentary have this belief because they state that people use banks "Because they know those payment systems and financial institutions are closely supervised by the Bank of Canada and other regulatory agencies." They also cite that Canadians know that their money is protected by deposit insurance. I doubt very many people are really aware of deposit insurance or how it works. And even fewer people care about how banks are regulated.

Without any legal framework at all, I'm sure many people would be happy to keep using RBC or TD as their bank. To say that none of the safety or popularity of banks is due to the banks themselves is clearly not correct. The authors cite the Bank of Canada for this, but it's not surprising that the Bank of Canada believes that regulators are the reason for why good things happen.

Google doesn't claim that regulation is the reason why they have the most popular search engine. No one does. And that's not due to a lack of regulation, it's because it's obviously a technological product. Similarly, banks rely massively on technology and international standards used by banks around the world. Banks are heavily regulated everywhere, but that doesn't mean the regulation caused their success.

It could easily be that Canadians are being negatively impacted by regulation, since it appears to be at least one part of the puzzle for how a small number of banks have attained such a dominant position for so long. Fintech competitiors don't have nice things to say about this situation.

The rise of technology companies, with hardly any "regulatory framework", let alone "strict regulation" is a rejoinder to the view that regulations are a big help to markets and innovation. Regulation is not a necessary element of everything people want to use, and it in many cases has been judged in hindsight to have been a hindrance. (I'm using "regulation" in the sense of the authors, not the broader sense of the word.)

I'm not an expert at banks or payments' systems, but I can see the wide variety of laws worldwide and guess that it's not that the laws cause "good" banks. Whether or not regulation is the most important factor, it's probably not the main determinant of the success of banks in a jurisdiction, since the banks themselves play a huge role. And if they don't play any role, why have banks at all? Why not just have the Bank of Canada do banking? That would seem to be better if you believe that the regulation is the key to good banking.

The Need For "Strict Regulation"

On page 9 the authors call for "strict regulation". Most people are in favour of "strict" regulation, because who wants "loose" or "flimsy" regulation? In reality, most of the Canadian economy operates under this model and it works fine. There are many pillars for supporting success, and regulation is just one. For example, there's a profession of accountants in Canada who are very good at making sure the numbers add up. A successful private stablecoin would be using their services, and the more popular the stablecoins get, the more that customers and other parties would demand increased independent accountant oversight. This is already being seen in the private stablecoin market.

The authors say that strict regulation is needed to prevent a "run" on a stablecoin, but that is only a problem if they're operated like banks are, which is to say a model where they actually don't have the money. That's not the case with most private stablecoins, and customers can choose whether they're fine with that model or not. Later in the commentary, the authors suggest that a law would require deposits with the Bank of Canada. But rather than require that, why not just make it available? If there was such an offering by the Bank of Canada I think it would be immediately embraced by stablecoin projects around the world, but it doesn't, and probably never will. This shows the difference in mindset between making new products available, and taking away opportunities. The former leads to innovation, and the later might still allow for innovation, but is rarely the cause of it.

Do People Prefer Oligopoly?

The authors are of the view that consumers prefer oligopoly/monopoly:

"History has shown that Canadians and the firms with which they transact prefer using only a small number of payment platforms: VISA and Mastercard, for example, replaced a plethora of credit cards issued in the 1960s and ’70s, while Interac dominates debit card payments."

I'm skeptical that Canadians love not having a market with many competitors. But it is obviously true that payments work best when they're compatible, since virtually everything does. But compatibility in the 1960s is different than today. There's no need for special hardware devices in a world of software, and compatibility is something that can be easily programmed. Uniswap provides thousands of cryptocurrency pairs for trading, and users can add new ones. ERC20 provides a standard for tokens. Why can't payments work like that too?

Consumer preferences are difficult to identify, and in any event not particularly relevant in a world of offerings like Interac. Interac was actually created by the largest banks in 1984. It's not the product of a competitive environment, it's a product of the opposite: a captive market, created by regulation.

When there's limited competition, it's easy to be number one. Open technologies change this dynamic. Suddenly there are choices. The Internet consists of hundreds of millions of websites, made all over the world by people speaking thousands of languages, and yet all of it is accessible through standardized web browsers. Open platforms permit competition, which drives down fees and improves the offerings available to people. This is a key advantage for cryptocurrency, which doesn't depend on monopolies or laws for its advantages.

No Risk Of Loss

The authors advocate for strict laws that result in "virtually no tolerance for risk of loss" but that's a fantasy in the modern world. Whether it's inflation eroding value, or significant changes like the globalization of Asia, there's always risk. But there's also immense opportunity. This isn't sophistry - innovation in banking and payments is good. People need more options, not less, and they need a wide range of risk to properly account for their circumstances. Would you prefer a private stablecoin that's free to use, and produces monthly accountants' reports that tell you that every dollar is there, or would you like a stablecoin that costs $0.50 to send $50 like e-Transfers? Maybe you'd like both.

At the moment, private stablecoins are quite small in their size and impact. To start looking at how to eliminate risk at this early stage in the game means eliminating innovation and ceding that field to other countries. And then eventually, Canadians will be using foreign services, with even less oversight from the government.

It's almost sacrilege in modern Canada to suggest that regulation won't make things better. Yet, almost everything in Canada takes place within a general framework of rules, rather than specific laws, and this is quite a good approach that's carried Canada forward for over a century. No one believes in simply cranking up regulation across the board, and yet many people cheer for "more regulation" as if there will surely be good outcomes.

It's easy to suggest that regulation will eliminate risk, but risk can rarely be eliminated, it's usually just moved somewhere else. And if it is eliminated, it means there's no upside, because risk and reward are two sides of the same coin. On page 11, the authors bring up the Bank of Canada providing liquidity to stablecoin creators, but that "liquidity" is not free either, and there's a degree of moral hazard in allowing the government to take on a contingent liability like that (which tends to look good on the books, but can cause huge losses if the contingency happens).

Unconditional Acceptance

The commentary suggests that "unconditional acceptance" is an important feature to a stablecoin, but that's obviously not the case since no stablecoin today has that feature. And Canadian Dollars don't have that feature either, in 98% of the world. For almost every practical purpose, being able to rapidly exchange one type of money for another, at a very low-cost, eliminates the issue of conditional acceptance because the bearer can just switch it to a form that is acceptable. Technology can solve this, and it's already how virtually everything works. For example, using a credit card in another country. (And stablecoins can make forex trades like that even cheaper than they are today.)

Decreasing Government Debt

A common argument against private stablecoins, and one that the C.D. Howe commentary authors make (pg. 12), is that if stablecoins (or foreign dollars, or bitcoin, etc.) gain ground then there's a risk that the Bank of Canada won't be able to "fully support" the government if it can't raise money in debt markets. But that only occurs when people don't want to buy the debt at the private the federal (or provincial) government is offering. Without the Bank of Canada's ability to print dollars (which is effectively taking value from people who have dollars already), they'd be forced to offer a better rate to investors. It's not that they couldn't borrow money, it would just be more expensive. This world is a very long way off.

Let's assume that C.D. Howe's concerns come to pass, and one day the Bank of Canada can't just print money if the federal government doesn't like the rates on offer from the international and domestic bond markets. If this was known and accepted, it wouldn't be an issue because it would instill financial discipline that would prevent this problem. If consumers have chosen to abandon the Canadian Dollar to such a degree that money printing won't produce much money, and the federal government can't sell its bonds, I don't think it's fair to blame stablecoins for that situation.

Printing Money

No mainstream economist in Canada thinks that the government can print or borrow infinite money. There's disagreement over the limit, or the effects as we move closer to that limit, but there is some sort of rough cap on this. Slightly moving that needle more in favour of restrained spending, in order to gain the benefit of what must be a much better form of money, is probably a great trade-off because the increased economic activity would be a benefit to the government that's taxing it.

The authors write, on page 13, "The Bank of Canada effectively would no longer be the monopoly supplier of the currency used by Canadians and in the economy more generally." But that's not even the case right now, as many businesses use the US Dollar for transactions and sometimes even bookkeeping.

Are We Going To Backslide To The 1930s?

The authors on page 13 repeat a commonly expressed viewpoint, that if Canada didn't have the Bank of Canada, with an independent monetary policy, then we would suddenly go back to the 1930s and whatever financial disasters they experienced. I'm not a historian, but Canada in 2021 is radically different than 1930. 90 years later, so much has changed, and I don't those concerns have much relevance.

The authors state that "Canadians thus should think twice before abandoning the Canadian dollar as the unit of account in their economic and financial dealings: the microeconomic gain might not be worth the macroeconomic pain." But almost everywhere in the world doesn't use the Canadian Dollar and they're fine. Would there really be riots in the streets if Canada switched to using the Euro or US Dollar?

What Is A CBDC? Does It Need "Blockchain"?

On page 16 the authors get more specific. They propose a system that seems no different than the idea that a central bank should have accounts for everyone (a somewhat popular idea in the US):

"Alternatively, with an account-based CBDC, Canadians could have their own accounts at the Bank of Canada. So, using the same example as above, I would perform the same digital transfer of funds to my sister as before, but I would do so from my own bank account at the Bank to my sister’s account at the Bank. The Bank of Canada would be the central ledger checking that I am who I say I am, and that I have enough money in my account to transfer the funds to my sister, with the ledger also validating that she is who she says she is."

What's described on page 16 is not a cryptocurrency, and would probably not be compelling for most people, unless it meant lower fees (but good luck with that idea in Canada, where banks have some of the world's highest fees and profit margins).

Having the Bank of Canada be the sole player in the system negates basically all of the advantages of cryptocurrency. Cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum are only useful in a context in which there is no central player that can be trusted to run everything properly, because if you had that, there's a way to achieve the same transactions per second with one billionth the cost. Centralized systems usually don't need blockchains, and almost certainly wouldn't if the central bank of a country stood behind the system because the very idea of the currency depends on their actions. If they can make or delete money on demand, how does a blockchain help?

Then there's the downsides. The authors acknowledge that a centralized system would have an important drawback: "In a Bank of Canada account-based system, this anonymity would be curtailed or disappear completely, with loss of privacy the trade-off." Not many users are going to be keen on reducing their privacy even more, unless there's a significant upside to them of using the CDBC. Fortunately, the authors aren't a fan of the idea of a centralized central bank digital currency, and instead a hybrid model of semi-decentralization that they call a "token-based system" (page 19).

Is It Worth It?

The authors of the C.D. Howe commentary conclude by suggesting that the "token-based system" would be carried out by banks. Would that be particularly different than today's digital cash? Not many people actually use banknotes, and instead rely on their bank payment methods, which would seem to bring us right back to the status quo.

It's probably not worth upending Canadian banking and central banking law and policy in order to try to compete with private stablecoins using a new type of money that there isn't a huge public demand for. No country has done this yet, and it's possible none of them ever will, because they may pursue different models. To the extent that a CBDC merely further entrenches Canadian banks, and the Canadian Dollar, what will Canadians lose? And if they lose too much, might they switch to the Chinese government's CBDC that's currently under development, a private offering from Facebook, or a private offering from Canadian companies that offer a range of stablecoins? The authors would likely say that the "strict regulation" they have in mind would make all of these unlawful, but that's hardly a constructive path forward.

Globalization has a way of making borders porous, and particularly so for digital transactions. There are many people today using Chinese fintech wallets like that of Alipay to make local payments that draw on their Chinese bank account. The globalized world is here. Cryptocurrency is here.

It's time to start looking at ways of radically improving systems and designing them for use because it's no longer about local laws and local competition. If the government is going to make any moves in this space, the ideal move would be to make a new system that the whole world wants to use. Nothing would be more beneficial to the Canadian government's ability to carry out policy than for the Canadian Dollar to become a widely used international currency, complete with thousands of tools and services that make financial transactions as easy as other online interactions. This world is technologically possible today, but conceptually still too far away for many people to seriously grapple with. The C.D. Howe commentary is a great place to start, and a good way to see what serious government organizations (like OSFI) think about these issues, but they don't light the way to a world in which the Canadian Dollar is ascendant. Rather than focusing on government convenience, a focus on how to make the Canadian Dollar a global champion would be a much better frame for judging any transformation of the money system.