The first part of this series examined the crypto lenders that took the blockchain world by storm a few years ago, and ended in several high-profile bankruptcies. This post looks at what the laws about lending are, and the arguments for why these crypto lenders weren't violating laws (despite the SEC & state-level settlements that say they were). This post completes the necessary background to understand the next part in this series, which is about the government's response in Canada to the failures of crypto lenders in the US. The first half of this article explains the background on various sorts of credit products, and then the second half gets into the specifics of the legal arguments of the now-bankrupt crypto lenders.

Familiar Lending Models

Before getting into the complicated world of BlockFi and other crypto lenders, it's important to take a step back to look at the general legal landscape of credit and debt.

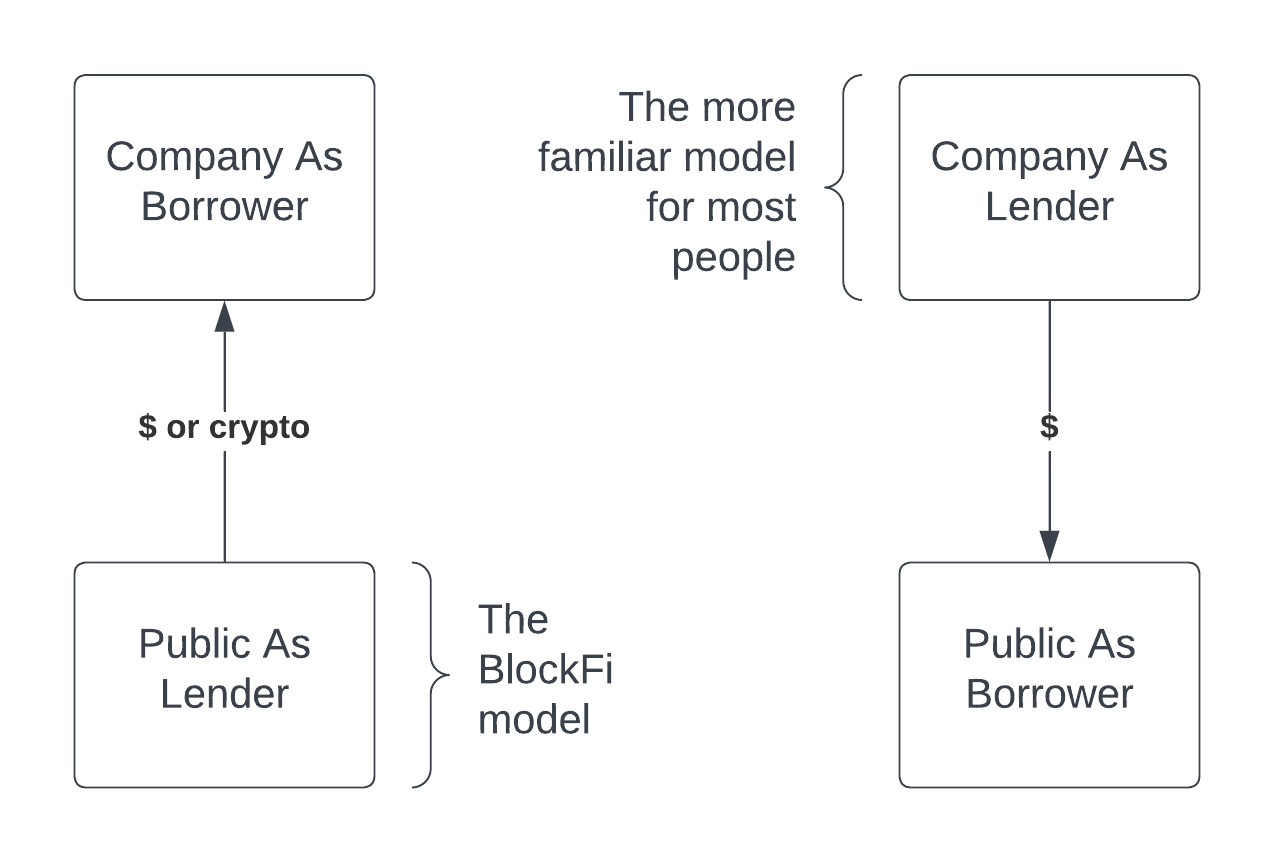

Most people are familiar with banks. Most people have at least some understanding of what banks do, which is to take the public's money and then lend it out. Banks actually do much more than this, and modern banking is not at all like how banks first started off in the medieval era. But it is certainly true that banks do take deposits and lend out money. They grant mortgages, provide credit cards, and many other types of debt products to the public. This is permitted by banking laws throughout the world. This type of license works like the right-hand side of the above diagram, with the bank company as the lender to the public. Legally, banking is usually an exception under securities laws, which carves out the banking space for banks, from the general rules that apply (explained later on in in this article).

The BlockFi's of the world (see previous post) were not banks (and still aren't banks). But banks are far from the only lawfully permitted lenders (or borrowers). These companies engaged in borrowing from the public and lending to the public. But it's only the former activity, borrowing from the public, that ended up causing trouble for them. The two may sound similar, but may be captured by separated legal regimes. This is an assymetry that results from the ways laws are enforced and the traditional activities that led to these laws in the first place.

It's very hard to start a bank and takes years, so the BlockFi's of the world did not undertake their activities within the scope of a bank license. It takes years of work and lots of capital to start a bank (although it's easier in America than Canada). That's not startup-speed. So companies like BlockFi, Celsius, and others looked to other kinds of lending possibilities. Fortunately for them, banks are far from the only entities allowed to lend or borrow.

The other possibilities for lending include a variety of non-bank lenders, such as, in the US, state-licensed lenders. Some of the crypto lenders that previous blog post looked at actually were licensed as state-level lenders for their outbound lending program. But these regulatory regimes don't cover borrowing from the public. Readers may also be familiar with other sorts of non-bank companies that lend to the public, such as mortgage companies (e.g. First National in Canada), payday lenders, pawn shops, etc. There are many kinds of lenders, or providers of money in a way that is similar to loans, and these operations are carried out under a variety of different regulatory regimes, or no specific statutory authority.

The Diversity Of Credit Provision In Modern Economies: Trade Credit

One of the biggest sources of financing in North America for businesses is scarcely known to the public and doesn't take place through banks or investment companies: trade credit

. Trade credit is offered by service providers (i.e. 30 days to pay an invoice). The trade credit model is common in the context of short-term lending to customers of a business, including other businesses. Some large companies demand of their suppliers that they accept payment up to 6 months after receiving the services/goods, and they rely very heavily on their suppliers to effectively lend them money at 0% or near 0% interest. This is often taught in MBA programs as a way to reduce the need to draw on bank loans and other types of financing (at the expense of suppliers, who are turned into lenders). According to a 2021 journal article, trade credit accounts for about 1/3 of financial liabilities for US firms. But trade credit was is not what the crypto lenders mentioned in part 1 of this series relied on in terms of legality.

Non-Loan Financial Products

Businesses might be familiar with other sorts of non-loan financial products, such as merchant cash advances

, that are not loans, and not generally covered by lending laws. One example of the merchant cash advance model is Stripe Capital, which is offered by one of the largest payment processors for small businesses in North America.

Merchant cash advances are well-established in some industries, such as restaurants and other merchants that have significant credit card-based receivables. Merchant cash advances are a multibillion dollar business in North America and fulfill many of the same purposes as bank loans. Although interesting, these non-loan products aren't at issue with the crypto lending companies that the rest of this article is about.

Key Laws

There are many legal regimes that might apply, depending on the details and the specific regulators involved in North America:

State/provincial securities (investment) laws, and in the United States: federal securities laws, are a major category. Banking laws and lending laws may also be relevant. Then there's a host of consumer protection laws that might apply depending on who the customer is. Commercial laws might apply, which can be codified or common law. Even criminal laws might be relevant, such as Canada's federal prohibition on certain kinds of debt having an interest rate above 60% (expected to be lowered in the coming years). And a hodgepodge of specific local laws that might apply to certain lending or borrowing activities, such as laws about co-ops.

Credit To Public vs. Credit From Public

Before going further, it's important to distinguish between two major kinds of debt: lending to the public vs. lending from the public. Lending to the public is a relatively common business model (done by, most obviously, banks but also others), but borrowing from the public is a different type of activity.

In the public to company form of borrowing, the term public

means anyone, not just rich people. Rich people have their own special types of investments that are available, which are forbidden to most of the population. This is called the accredited investor

exception to securities laws, which is based on the premise that rich people need less protection from the government in terms of making bad deals. That principle may not be true (rich people often don't know much about investments), it may be class-biased (should opportunities be denied to people based on wealth?), and it certainly limits the investments available to 99% of the population (by design), but whether or not people like it, that's the general rule for investments in North America. If an activity falls within these rules, it very often can't be done, because this is a tightly regulated area. Securities laws are some of the most complicated legal regimes that apply to businesses. The Ontario Securities Act statute clocks in at almost 80,000 words (without regulations, guidance, case law, and much more that brings the total to thousands of pages of applicable laws).

The savvy reader may be wondering right now about various stock market opportunities available to the public which pay out on a percentage basis, such as periodic dividends from profitable companies or monthly yield on money market funds. These are regulated by securities laws (discussed later on), and subject to many rules. These are also not the kinds of opportunities that BlockFi and the other crypto lenders were pursuing. They were attempting to create a new, global, category of borrowing from the public outside of that framework.

Creative Approaches To Debt As A Business

Debts occur regularly as a result of people not paying for things (e.g. not paying a home contractor), and legal actions on debt are widespread. But these are not companies that are engaged in debt as a business, that is, a business where dealing in debt is the business, rather than a side effect of another activity. This is the business of debt itself.

What's of most interest to entrepreneurs is figuring out ways of offering the ability of the public (i.e. non-accredited investors/rich people) from engaging in direct activities in which their money is put into some sort of system that results in more money (despite the general prohibition principle). This was the business model of BlockFi, Celsius, and Voyager Digital before they collapsed (see previous post for details).

The Consumer Protection Role

Direct provision of credit from the public is inherently more difficult than credit to the public, because governments care much more about protecting the public than they do the companies that can usually look after their own money quite well (e.g. underwriting standards). If there were no laws at all, lenders would still be carefully scrutinizing who they lend to, and avoid loans to those who are unlikely to pay them back. The public, without access to the knowledge of how to do that, and without the resources of companies, has a much harder time scrutinizing deals, and so it is logical that regulators would pay the most attention to this side of the equation.

Transaction Costs And Provision Of Credit

Credit from the public is rather unusual. There are far fewer examples of this in part because of laws, but also because it's normally rather difficult to organize lots of small dollar amounts. It's only in the last few years of digitization that it's been practical for small dollars to be grouped together into big results, with low enough transaction costs. In the traditional investment world, digitization has caused a tremendous shift in activities from gatekeepers (e.g. stock brokers) to self-serve platforms. This process has shifted so far that Robinhood, a major American stock service, managed to figure out how to offer $0 stock trades to regular investors, without any dollar minimums.

Tremendous advancements in business models and reductions in transaction costs are a part of the ongoing movement to make financial services more available. This technological advance has paved the way for companies to approach the business model of taking in money from the public and paying out some sort of proceeds.

The General Prohibition

The Canadian and American securities statutes generally forbid people from taking money from the public and putting it into investments (that go back to the investors). The approach of this system is to forbid everything, and then allow a few holes to be punched through the general rule, such as investments by friends and family of the company founders, rich people investing, or of course the most familiar exception: the stock market.

The public is not very familiar with the general prohibition that prevents them from accessing many kinds of investments that aren't on stock markets. Surely many people would agree that they should be forbidden from accessing these investments, but others are very interested. This has especially been the case in the low-yield world that dominated for many years in North America in which bank accounts pay under 1% per year in interest. The low-interest environment caused many people to look for interesting alternatives. BlockFi, Celsius, and others stepped into this market.

The large crypto lenders that went bankrupt in the last year (see previous post) were not a few people in a garage borrowing billions from the public. They hired some of the best lawyers in America (and elsewhere) to advise them. These lawyers wrote them memos that didn't say your business is unlawful and you need to stop

. What is in those memos is a privileged secret, but the contours of this advice can be seen in the legal strategies that they pursued.

Gemini Earn's Argument

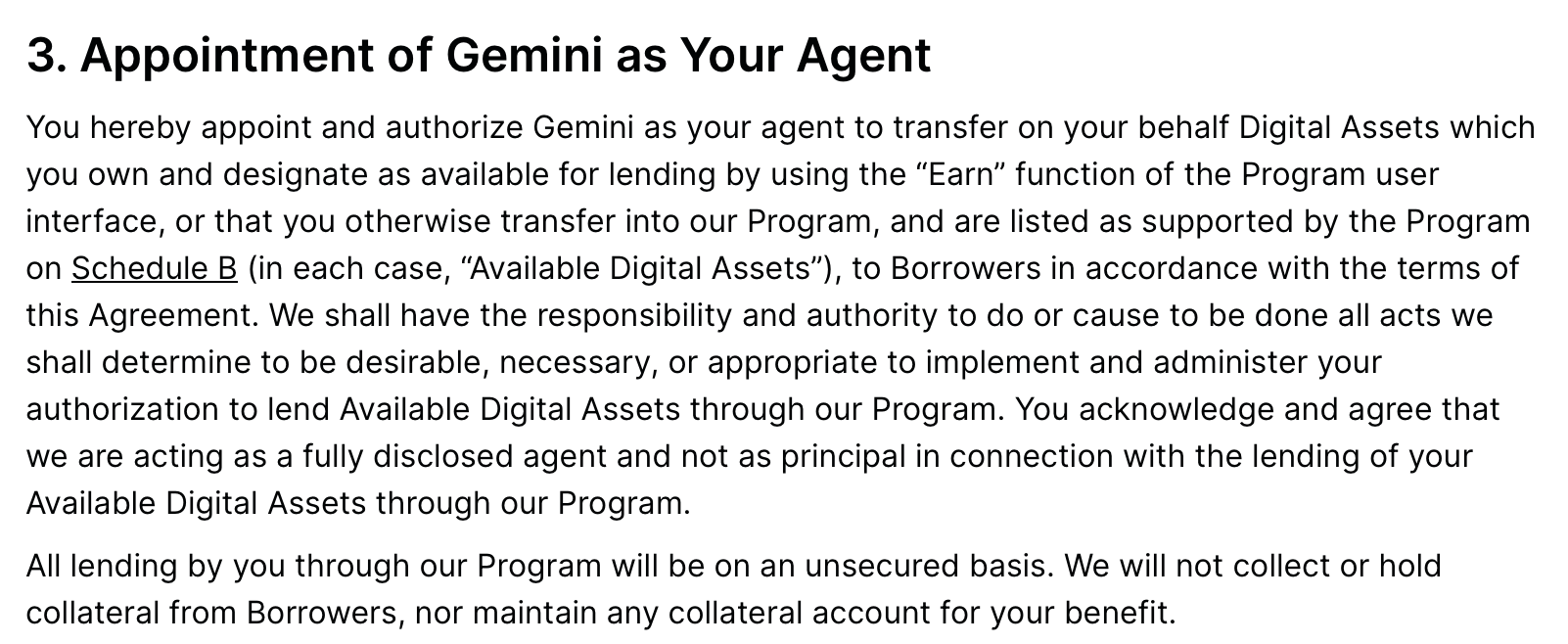

Gemini Earn (currently the subject of SEC action in the United States) had a rather unique positioning for their product. The legal terms for Gemini Earn stated that they were acting as the agent for the individual. Agency is a fascinating area of law that most lawyers aren't too familiar with, and the public even less. But it's an old doctrine that can be used in interesting ways. Someone at Gemini headquarters, or more likely, at their law firm's offfice, came up with the idea that they weren't borrowing from the public, they were merely helping the public to lend to other people.

The SEC's allegations against Gemini (jointly with Genesis - see previous post for explanation) describe the agency relationship as:

To participate in the Gemini Earn program, Genesis and Gemini required that investors enter into a tri-party Master Digital Asset Loan Agreement with Genesis and Gemini (“Gemini Earn Agreement”), whereby Gemini Earn investors provided crypto assets to Genesis, with Gemini acting as the agent in the issuance. Genesis would send interest payments to Gemini, which would then deduct an “Agent Fee” before distributing the remainder of the interest payments to Gemini Earn investors.

Was Gemini really acting merely as an agent for the account holders? Does that actually permit their activities (since being an agent for securities transactions may be unlawful too)?

The US government claims that Gemini was selling unregistered securities to the public. The SEC states that Gemini decided the in-kind interest rate on the crypto that was supplied to them by the public, and they had the unilateral abiltiy to change the rates paid. Gemini had sole discretion over how much they took (the agency fee

) from their customers, and the interest rate paid, which determined the net rate paid to the customers. The SEC doesn't spell out their argument in their allegations, but presumably their view is that this was itself an investment contract, and that it is not an agent-principal relationship.

Perhaps the idea Gemini had in mind was that it was actually the customers engaging in the transactions (directly), not Genesis, and that was what made it proper. They perhaps had in mind something like Uber, in which Uber claims that they don't provide taxi services, they merely connect users with drivers. As of early April, 2023, Gemini and Genesis have not yet had an opportunity to explain their case publicly in court, so the story can only be filled in with conjecture. Undoubtedly the millions of dollars these companies spent on legal fees resulted in some good arguments, but these haven't yet been aired.

One problematic part of the story for Gemini is that if they weren't engaged in offering investments, who was? Since the only other company involved was Genesis, it's not surprising that the SEC has pursued a case against both companies together (which is rather unusual in the world of cryptocurrency-related litigation by securities regulators).

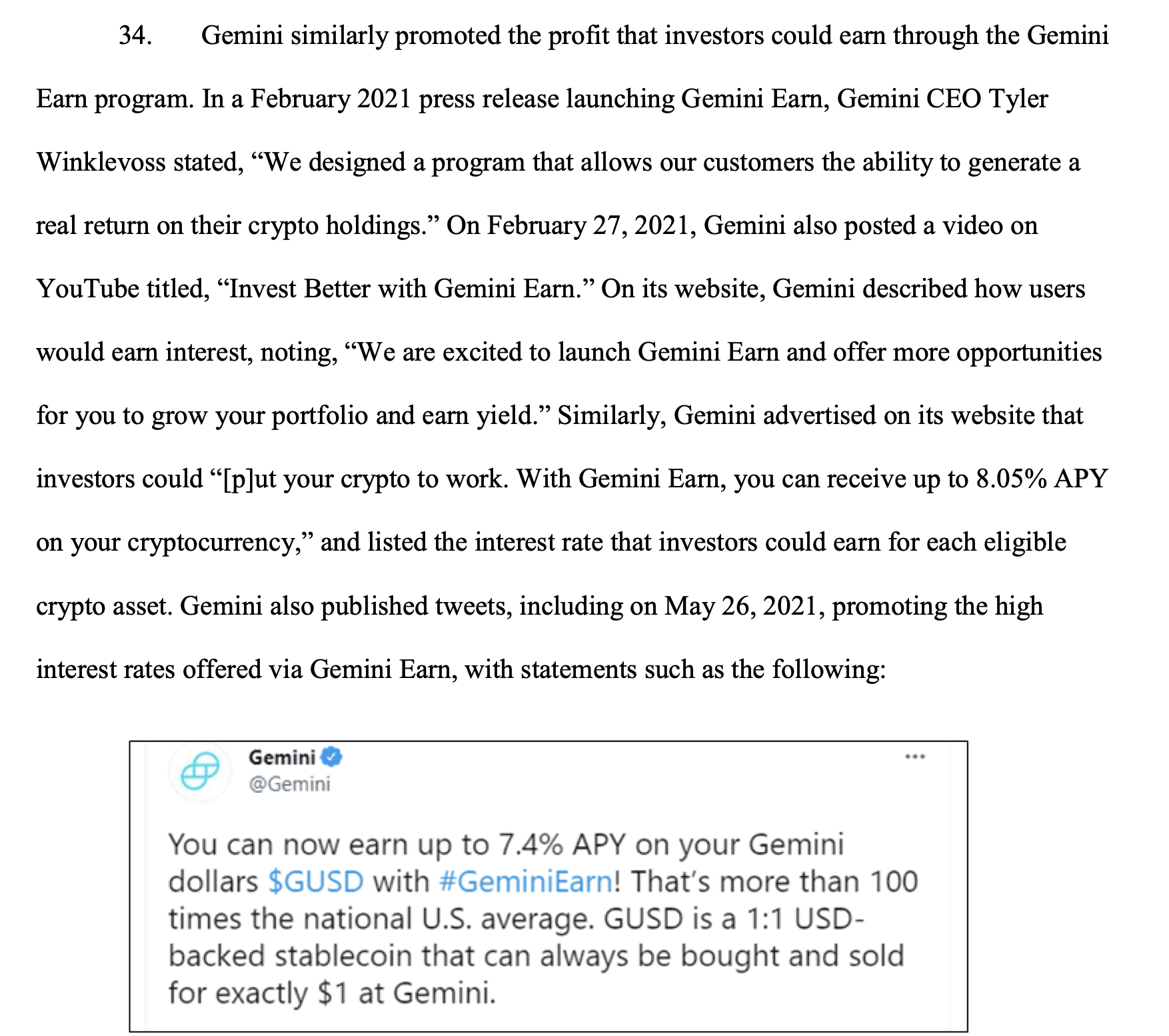

The SEC provides further examples from the Gemini Earn website that described the activities as "investing", "investment decisions", "option to invest", and other language that's not favourable to the case that they were not handling investments (let alone the SEC's case that they were actually offering investments themselves to the public, not merely an agent for others to do so).

Transacting in unlawful securities is unlawful (unsurprisingly) in the same way, under the same laws. Securities laws have very few loopholes

, in part because of a century of statutory reforms that have tightened the laws, but also because securities laws are deliberately designed to cast a very wide net, with discretion to decide who to pursue handed to the various regulators. Both Canada and the US follow this pattern. This makes it hard to say whether some things are securities or not, but it also gives the government a wide statute to support actions like the SEC's case against Gemini/Genesis. Likely the crypto lenders' legal counsel also viewed this contested space as an area where they might be able to carve out a new class of companies that operate in the world of credit.

Gemini's Response To Legal Action Against Them

What does Gemini think about the SEC's litigation against them? In recent days, Gemini co-founder Tyler Winklevoss has tweeted out his general opposition to the government's wide-ranging powers, but it's not particularly illuminative of their legal strategy.

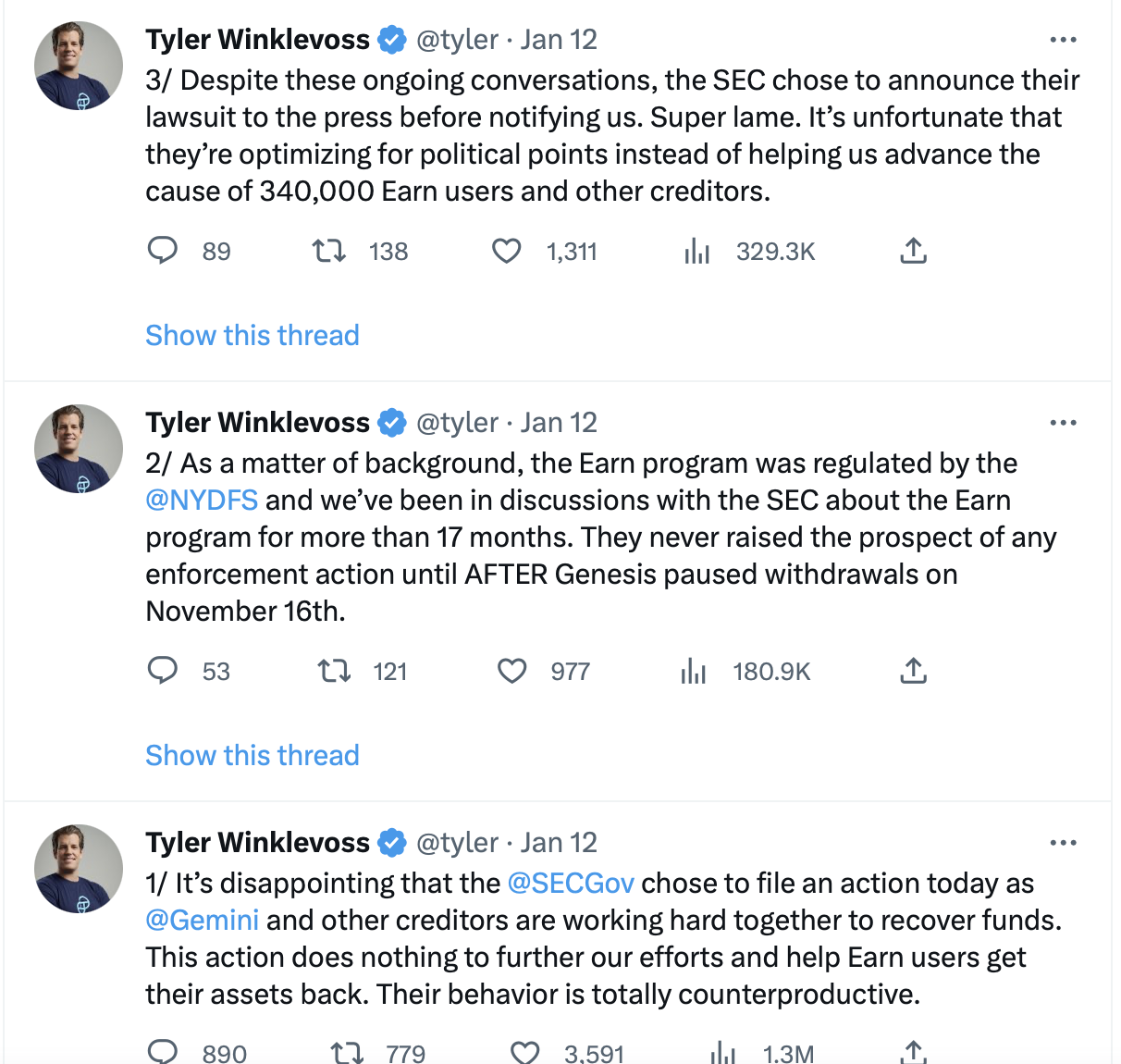

Around the time of the SEC's lawsuit, Tyler had more direct comments on the litigation, which reveal a little more about their thoughts on the Gemini Earn program.

Gemini's Earn program was run by a limited purpose trust charter

regulated by the NYDFS (a state-level regulator in New York). They were originally approved in 2015 as a cryptocurrency exchange. Is Gemini Earn permitted within the scope of this New York state-level licensing? Does a state-level permission trump federal securities laws? The latter is a legal issue I can't say much about as a Canadian lawyer, but it may not be very important because the regulatory authority (NYDFS) issued a statement in January that seems to indicate that they don't approve of the Gemini Earn model:

VCE Custodian’s Limited Interest in and Use of Customer Virtual Currency: When a customer transfers possession of an asset to a VCE Custodian for the purposes of safekeeping, the Department expects that the VCE Custodian will take possession of the customer’s asset only for the limited purpose of carrying out custody and safekeeping services, and that it will not thereby establish a debtor-creditor relationship with the customer.

The agency argument may be put to rest by the SEC's litigation against (the now bankrupt) Gemini/Genesis, or perhaps there'll be a settlement. But it's also possible that Gemini will pursue the legal argument that they based their service on, and argue successfully that they were an agent, and that the agency relationship means that if anything was done wrong, it wasn't done wrong by them.

It remains to be seen whether Tyler Winklevoss's statement about the NYDFS regulating them is meaningful. Did the NYDFS regulate some of Gemini's business but not all of it? That seems to be what the NYDFS is saying, and that's a logical interpretation in one sense, in that a regulator doesn't always have statutory oversight of every part of a business, but they do have holistic oversight authority. This may be a semantic matter that's useful for PR, rather than an important legal point.

The agency argument of Gemini shifts the burden over to Genesis. But it's possible to imagine a different situation in which a Gemini Earn program is an agent that helps users to connect with other opportunities that are either distributed (in the same vein as Uber drivers and Airbnb hosts not being a single corporation that can be pursued) or that are decentralized applications (i.e. true DeFi). The agency argument is probably not dead yet, but it may be tested by the SEC.

I leave it to securities lawyers and judges to debate whether the agent role really means that the company has stepped out of the securities picture, but this seems to be the core of the argument that Gemini's lawyers constructed for their Gemini Earn program. But so far, Gemini's argument does not seem to have protected them from regulatory action at the federal level in the United States.

Other Models: BlockFi' Borrowing From Customers

Agency is not the only model. BlockFi (also backed by the Winklevoss brothers, and by 3AC) and Voyager Digital didn't claim to be agents acting for their users. The legal terms for BlockFi's service help to understand what they were doing (pre-bankruptcy and SEC litigation). They can be found on the Wayback Machine (a favourite tool of mine for researching companies, since they are sometimes more candid when they start than once they're a billion dollar enterprise).

BlockFi accounts were, a few years ago, permitted for people all over the world, except certain places subject to sanctions like Cuba and North Korea, and also prohibited in New York (probably due to the state-level BitLicense). They called the accounts crypto interest accounts

. They describe the whole thing as paying interest

. The user consents to BlockFi making use of the crypto that is in the accounts in a variety of ways, including to invest

it. These words came back to bit them later, as the legal terms were part of the documentary evidence that the SEC used to further their case against BlockFi.

BlockFi must have viewed the activity of paying interest as not being a securities or banking transaction. How might that be the case? There aren't many analogous products that pay interest to customers. Typically it's the customer paying interest to the company, on overdue bills, rather than the other way around. Securities lawyers I've spoken with say that these kinds of products are always securities, but BlockFi must have thought differently, or they would have realized that their product was unlawful. Could it really be the case that they thought that they were running an illegal business, and all of their venture capital fund investors thought that too, and they still operated for several years at a billion dollar+ scale?

Perhaps BlockFi didn't consider the SEC's argument that they were actually selling notes

(under the common law Reves test)? If they missed that one, could they have thought that what they were selling wasn't an investment contract

as the SEC alleged? Or that the entire business wasn't an investment company

? It's tough to look at the SEC settlement and not see a variety of risks that surely BlockFi's lawyers knew about. Unfortunately the settlement doesn't explain why BlockFi thought they weren't offside.

One possibility is that BlockFi thought that they could change the law to permit their model (i.e. beg for forgiveness rather than permission). The biography of their general counsel (still available) notes that he worked for traditional lenders like Deutsche Bank and Barclays and is now working at BlockFi as an helping the company emerge as an active participant in ongoing regulatory conversations as the crypto regulatory landscape continues to evolve

. That's not a great legal strategy, but it is true that many financial innovations have been offside at first, then become regulated and legalized through a dialogue between the pioneers and regulatory authorities. If that's what BlockFi was relying on, this has not worked out according to their plans.

A bit of trivia: the 2020 press release announcing the hiring of BlockFi's general counsel contains what is basically an ad for the interest-bearing accounts.

In the summer of 2021 there was an order against BlockFi in their home state of New Jersey alleging that their interest-bearing accounts were unlawful securities under state law. The order notes that BlockFi, on their website, fails to explain that the New Jersey Department of Banking and Insurance does not license the BIA, or that complaints should be filed with the New Jersey Bureau of Securities, because the BIA is a security.

This statement seems to indicate that BlockFi viewed their activities as being covered by their state lending license (which they did have), rather than being securities (which were regulated differently, and for which they weren't registered). If BlockFi thought this before New Jersey took action against them, they should probably have been on notice that securities regulators weren't buying that argument.

The founders of BlockFi responded to the New Jersey order by saying that they had this concern from the founding of the company:

In February of 2022, BlockFi's general counsel and one of the founders went to Reddit to assure users and the public that the SEC settlement was actually a good thing, and that they could cover the $100 million cost ("fortunate financial position"). By November of 2022, all of the BlockFi entities were bankrupt.

Curiously, BlockFi continues to offer their interest-bearing account product, but not to Americans (although a BlockFi customer wrote to me and said that even foreign accounts are paused as of early April). BlockFi's current offering is only to non-Americans, but it follows the same model as before. This is likely in jeopardy of attack by foreign regulators on the same basis as the SEC's action against them, since many countries have similar securities laws to that of the United States.

Voyager Digital

Voyager Digital is another one of the companies that engaged in the crypto lending model. Unlike the other companies, Voyager Digital was publicly traded, so there's a number of documents available in which they discuss the risks related to their business. These documents quite plainly disclose their business model of providing customers with crypto rewards paid monthly and in-kind to customers holding requisite minimum balances of eligible crypto assets in their Voyager Account

(from the first quarter of 2022's MD&A filing).

The Voyager MD&A document filed on SEDAR (the Canadian equivalent of EDGAR) for the last quarter of 2021 has little to say about the risks of their model, merely noting on page 25, in the Contingencies, section that:

[Voyager Digital] has been subject to non- public, fact-finding inquiries and investigations by both the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and certain state regulators in connection with certain offerings of the Company.

By the end of the first quarter of 2022, the Contingencies section of their MD&A filing (dated May 16th, 2022) was getting a bit more serious:

The Company, along with other participants in the crypto-financial services industry, has been subject to non-public, fact- finding inquiries and investigations by both the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and certain state regulators in connection with certain offerings of the Company. Between March 29, 2022 and April 13, 2022, the Company received cease and desist orders from the state securities divisions of Indiana, Kentucky, New Jersey, Oklahoma and South Carolina, and orders to show cause or similar orders or notices from the state securities divisions of Alabama, Texas, Vermont and Washington. These state orders generally assert that through the Rewards Program, the Company was engaged in the unregistered offering and selling of securities or investment contracts in the form of the Company’s customer accounts that permit customers to earn rewards on their eligible crypto asset balances. These state orders only apply to the Rewards Program and the remainder of the Company business is not affected by the state orders. The Company is in ongoing communications to better understand the terms of the respective regulatory orders, including any civil penalties, their applicable effective dates.

On June 9th, 2022, Voyager issued a press release that claimed that their program was only forbidden (so far) in Kentucky, but that they were the subject of a number of state investigations. The press release notes that there were other similar programs operating, and perhaps that was a part of Voyager's logic why they could operate to. This isn't a great legal basis for a program, but it's a common one! But Voyager probably had suspicions that all was not well. Five days after that press release, they issued another one noting that they had pulled assets out of Celsius because they had due diligence concerns. By July 5th, Voyager had issued a press release announcing they were undergoing a bankruptcy process.

None of the public company disclosures say much about Voyager's legal strategy. But their website (still available through the Wayback Machine) does. Voyager labelled their program a rewards

program that paid monthly rewards like clockwork

. Users could also get bonus rewards by owning Voyager's VGX token (similar to the model employed by Celsius of adding their own token into the mix, but this probably doesn't change much legally). The terms of the program permitted Voyager to pledge, repledge, hypothecate, rehypothecate, sell, lend, or otherwise transfer or use any amount of such cryptocurrency [in the accounts]

. Elsewhere they described their rewards program as having very little risk

, which obviously turned out not to be the case.

The Arguments Still Haven't Been Made

The arguments of the crypto lenders remain mostly unknown. Settlements are widespread in business and they don't necessarily indicate wrongdoing, or a lack of legal logic backing up a company's position. Though with billions of dollars of losses to the customers, the settlements and bankruptcies don't reflect well on their business models. And the system of securities regulation in North America is often less legally rigorous, and more outcomes-based. If your company causes people to lose billions of dollars, there's probably some sort of law that is applicable. With thousands of pages of laws at the federal and state level in the US, and similar regimes elsewhere globally, it's hard for some sort of regulator to not find a rule to apply.

Credit From The Public In Context

One lesson from the crypto lenders and their regulatory cases: credit to the public may be covered by banking/lending laws or maybe no statutory law, but credit from the public may cause the service to be viewed through a securities lens. Whether or not that's correct, it's what has happened, and will likely continue to happen.

The regulatory orders against BlockFi indicate that the securities regulators view this as a part of their consumer protection mandate. The New Jersey order against BlockFi notes that they got to nearly $15 billion USD in value at the time of the action against them. Their bankruptcy the next year does justify the consumer protection mandate post-hoc. But is that the only possible legal lens?

Enforcement Outcomes

Somewhat ironically, the SEC may be paid first instead of the customers, as part of the bankruptcy process. This is perhaps an argument for more proactive enforcement, or it's an indication that lawyers may not be providing appropriately conservative legal advice to would-be fintech champions like BlockFi (which is arguably one cause of the losses).

Being outside of specific laws (i.e. covered by common law rules or commercial laws) doesn't necessarily mean a company poses a danger to the public, but there are good reasons for why so many places in the world have significant restrictions on certain models of companies borrowing from the public.

Some types of minor borrowing

from the public are permitted (whether de facto or de jure), such as credits for refunds/returns or deposits on purchases, but these types of outstanding debts/deposits typically don't pay interest. The finer details of these sorts of systems are important to their legal characterization.

Had BlockFi not paid interest

, perhaps they wouldn't have run into trouble, but the interest was the entire point of the product because that's why people sent their hard-earned cryptocurrency. The interest was paid out of profits that they earned, on behalf of the users, and it's this aspect of the system that was integral to the claims against BlockFi on securities grounds.

Any company engaged in borrowing from the public ought to pay close attention to these examples because even though these are all settlements, rather than court decisions, the logic is spelled out. That's not to say that anything within the world of debt/credit is covered, but that lawyers ought to pay attention to these issues when a business is operating in a similar fashion to BlockFi/Voyager/Celsius. The SEC and state regulators didn't make their orders in a legal vacuum. And those regulators continue to pursue the same lines of reasoning in multiple cases. Canadian regulators can be expected to pick up this line of argument too in any cases that they're pursuing.

Part 3: The CSA Staff Notice

This blog post reviews some of the law about crypto lenders. Part 1 explained their business models. Part 3, which will be coming up, explains the CSA Staff Notice that brings these topics together. Stay tuned.

Disclaimer: This is a complicated area of law (or rather, the intersection of several laws), some of which involves America, a country where the author is not a licensed lawyer. There's a lot more to these topics, which fill many textbooks and the minutae of which consumes the lives of the lawyers who specialize in these areas. Some of the above article is a summary, some is opinion, and some glosses over important gaps or nuance. This is inevitable when writing a blog post. It's also not particularly fair to the companies involved because they haven't had the chance to fully articulate their legal positions due to bankruptcy and settlements. Please consult a lawyer before acting on anything related to this post, which is a high-level summary aimed at the public, not legal advice for your specific situation. This is complicated and the author is not an expert at some of the topics covered in this series, just a keen observer. Please let me know about any mistakes in the above, to better share knowledge about this interesting business model that took the crypto world by storm for a few years.