This is part three of a three part series. Part one explored the business side of various crypto lenders that have gone bankrupt, and part two looked at the legal side of these companies' pre-bankruptcy operations (which reached many billions of dollars of claims). This third part looks at the CSA Staff Notice that mentions these companies and proposes new restrictions on Canadian cryptocurrency trading platforms: CSA Staff Notice 21-332 (CSAN 21-332).

For the reader who is new to these sorts of staff notices: they are a way for securities regulators to public their internal thinking about an issue. Although theoretically not law, these staff notices are often treated by practitioners as if they are law, and they're an important part of the regulatory landscape in Canada. CSAN 21-332 is complicated. This blog post looks only at the parts of the notice that are related to credit/borrowing.

Credit-Related Provisions Of The Staff Notice

The motivation for the changes is explained in section 1 of CSAN 21-332 under the heading "Purpose". In this section, the explicit motivation for the staff notice is stated as being the failure of Voyager Digital, Celsius Network, the FTX group of companies, BlockFi and Genesis Global

(explored in depth in parts 1 and 2 of this series). As a recap, what happened with these companies was primarily about borrowing from customers, not lending to them (although some of the companies listed did that too). The Canadian provincial securities regulators (working through the CSA forum) decided that these failures called for changes in Canada (pages 1-2, and 4 of CSAN 21-332):

1.

enhanced commitments to preclude the unregistered [crypto trading platform] from pledging, re-hypothecating or otherwise using crypto assets held on behalf of Canadian clients2.

prohibition on the part of the [crypto trading platform] offering margin, credit or other forms of leverage to any type of client in connection with the trading of crypto contracts or crypto assets on the [crypto trading platform]’s platform3.

restriction on margin and leverage for retail clients

Essentially the regulators have decreed that they won't allow crypto trading platforms (or at least, the ones with the most common model globally) from continuing to operate in Canada unless they eliminate lending (to and from customers) from their platforms. It's noteworthy that these rules

(technically not rules, just an opinion) were not a part of previous consultations. Had platforms known that regulators would seek to continually restrict their businesses once the system starts moving, they might have opposed it more at the beginning. The CSA's explanation of the potential punishment for non-compliance is:

There is no assurance that the [crypto trading platform] will be registered or be granted its requested relief, and if it fails to become registered or obtain the necessary exemptive relief within a specified period, it will have to cease carrying on registerable activity in each jurisdiction of Canada in which it is not registered.(pg. 5)

Having entered the system of operating as restricted dealers, and acceding to the regulators' view of their authority, most trading platforms will have little choice but to continue with these new restrictions. But are these new rules justified by the events that the CSA cites as being the reason? Motivation is of course irrelevant to what the rules are, but it's interesting to take a closer look.

Disingenuous Premise In The Staff Notice?

The failures of the crypto lenders cited at the beginning of the staff notice seems unrelated to Canadian crypto dealers. The business model of these companies was not operating as crypto asset trading platforms (with the exception of FTX, which failed for a different reason). Yet they're cited in support of these new rules. Is this an example of never let a crisis go to waste

? My guess is that it's less that and probably more a matter of harmonizing the rules with that of other securities dealers (see below). Customer safety is always an element of regulatory systems, but if this was important for safety, it's surprising it hasn't come up in the last many years of the CSA's efforts. Credit, margin, and other borrowing concepts aren't new to securities regulators.

The Securities Lawyer View

Probably many securities lawyers would say that these new restrictions on credit are natural extensions of the securities law system. To a securities lawyer, it's not a debate to have, because it's the normal system. There are significant limitations imposed by securities laws on the credit that can be offered to buyers (i.e. margin

). And the borrowing from customers is something that may very well be covered by existing law (following the reasoning of American legal action on this subject - see part 2 of this series).

But if the existing law already prohibits it, why would securities regulators need to provide these new rules to prohibit it? Is it because the platforms were acting unlawfully before and it's simply a reminder? Is it a novel issue that no platform was engaged in, which is why there wasn't previous guidance or enforcement? These questions aren't explored in the staff notice.

Securities lawyers tend to see these sorts of restrictions as being natural because they see this process as being about analogizing over to how securities regulation works. But cryptocurrency itself is not often a security, unlike stocks or bonds (which surely are securities). This is not the same type of activity. It's not the same subject for regulation.

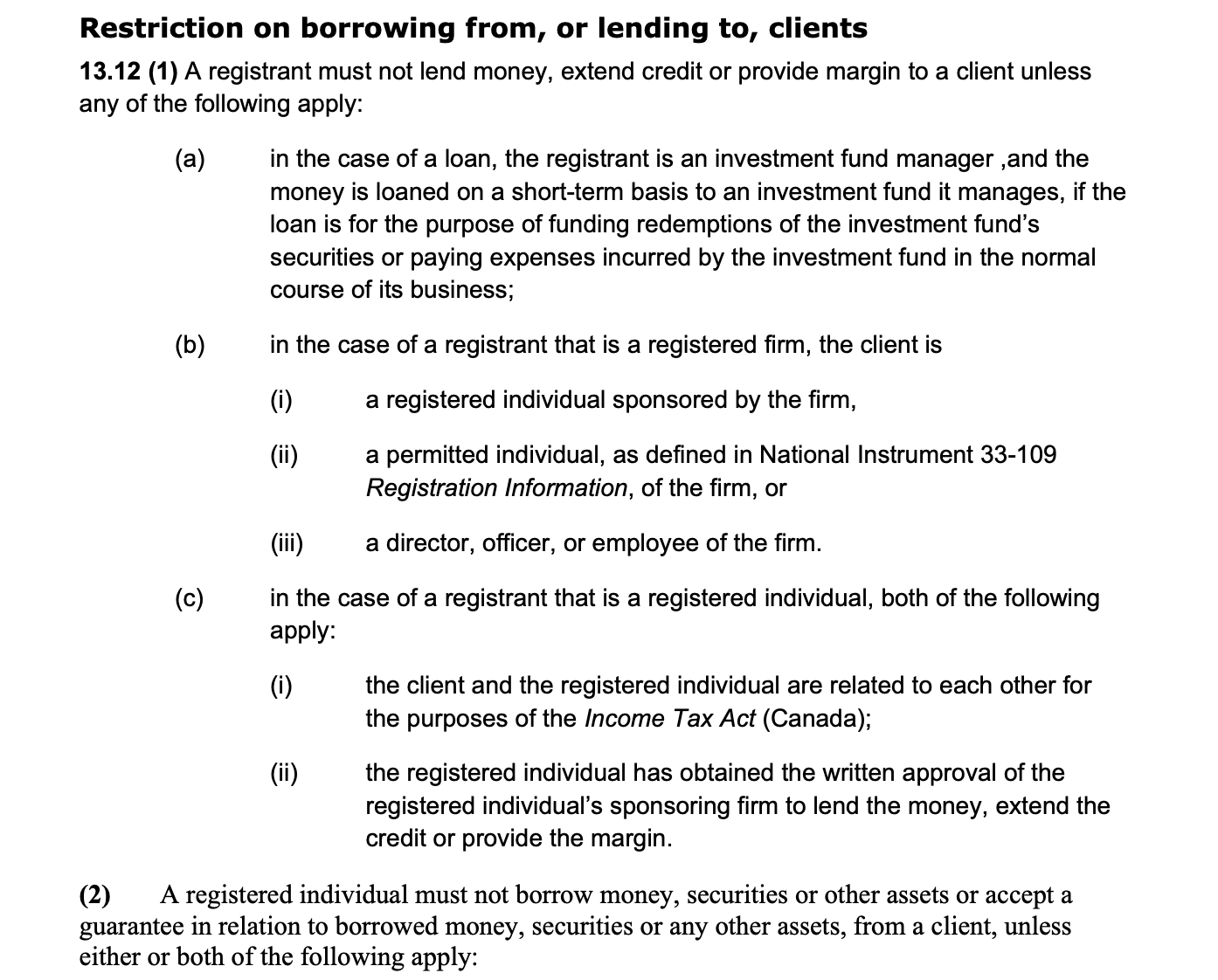

Is it correct to increase the regulatory burden to become like that of securities regulation? Is NI 31-103 (s. 13.12 reproduced in part below) the right model for cryptocurrency platforms? The CSA and its member regulators seem to think so. But the debate seems to be bypassed by a staff opinion that sidesteps the issues to say the platforms must not act in this way. Whether or not they can borrow or lend isn't important if the regulators simply won't allow a company to progress through the system unless they agree to not do something. This may be correct as a matter of securities law, but the logic isn't set out in the staff notice, which is a shame because they're quite interesting, and contested issues. A law firm would not get away with writing so little about the legal logic of the status quo vs. this new system. But the new system for cryptocurrency dealing is clearly based on the old system of securities dealing.

Restricting leverage is often seen as a laudable goal by people who operate in the Canadian securities regulatory regime. Warren Buffet, one of the world's most famous investors, once repeated his partner's warning that leverage is one of the three ways investors go broke. But it's also true that leverage is how many people have made their fortunes.

Offering and receiving credit is a normal, common practice that is widespread in the Canadian economy. But as cryptocurrency is subsumed within the Canadian securities regulatory regime, the restrictions on (consumers) from borrowing are an obvious move by regulators. Whether or not that's a good idea is not important to the discussion, because once the analogy is made, it would be illogical to not apply the same restrictions in the securities dealer world to the cryptocurrency trading world. CSAN 21-332 is a great example of this analogy at work, even if it's motivation may not really be as stated and the explanation is not as strong as practitioners might prefer.

Borrowing Risks Are Not Alike: Looking To The Future

What sunk the American companies crypto lending companies (that are ostensibly the motivation for the latest change in the rules) wasn't lending to customers, it was borrowing from customers. Yet the focus of CSAN 21-332 is much more on the lending to clients, which has not been the cause of bankruptcies. If anything, lending to customers is pro-consumer. The companies have a strong incentive to not let people borrow too much. And will prohibitions on borrowing from platforms really result in people not borrowing money through other means like HELOCs?

Borrowing comes in many varieties (see part two of this series for examples). If a company allows a customer to make a purchase and pay for it in 30 days (a common term for invoicing), that's a type of borrowing that's short-term in nature and makes doing business easier. Or, even less risky: lending against cryptocurrency held as collateral. There are lots of variations on credit that may not be like the sort of credit that the OSC and other securities regulators have in mind. A crypto trading platform might want to offer a degree of credit to a good customer who has sufficient assets to cover a collateralized loan. The effective interest rate on that transaction might be better than other potential sources because of their easy access to the collateralized assets. This is how loans in the MakerDAO system work (explained in part 1 of this series), which is entirely on-chain and operates (mostly) autonomously on the Ethereum blockchain.

If regulators in Canada foreclose credit possibilities, they'll drive opportunities away from the Canadian platforms and towards international, on-chain smart contract-based systems (which may be completely beyond the reach of regulators). That might actually be a good outcome, but to the extent that transactions move outside of Canada's borders, there's a risk of Canadians getting caught up in foreign disasters, like the failures of the crypto lending companies that are the cited reason for this staff notice.

There is a fine balance between ensuring that there aren't more holes poked in the securities system (which cryptocurrency shouldn't have much to do with), anti-fraud action, and ensuring that Canadians are able to access services that are common in other jurisdictions. The reality of the cryptocurrency industry is that Canadians will go offshore, as they have for many years (e.g.: MtGox in 2010-2014). Or, crypto platforms in Canada may simply become onramps into the DeFi ecosystems that are being built up on-chain. Either way, local businesses end up losing out.

Another way of looking at these new restrictions is that they're intended to be only relevant to cryptocurrency trading platforms that have the model that makes them a restricted dealer. Although that's a wide swath of comapanies, it's not every company. So it's true in a sense that the staff notice limited in scope. If a company stays out the dealing part (restricted dealer), presumably these rules wouldn't be relevant. But they would still be relevant to the extent that these new rules aren't new rules at all but are rather a restatement of existing law (following the same arguments made by American regulators).

Back To The American Examples Of Crypto Lending

Restrictions on novel business forms might be justified by disasters (a common rationale). And if Canadian securities regulators were moving only in the direction of preventing a repeat of the Celsius, Voyager, BlockFi systems from causing losses in Canada, that would be more understandable.

I doubt any of the large crypto platforms in Canada are actually opposed to rules that prevent massive insolvency risks to consumers. But that's not all the latest staff notice does. It goes further. The latest notice is expanding to block all forms of credit (perhaps not quite achieved with this guidance, but it's certainly a big step in that direction). Lending and borrowing are both the targets of the notice (although it may be less obvious how the lending part works due to the technical language in the notice).

Credit: Good And Bad

One of the marks of an advanced economy is the extensive provision of credit (via smart risks taken by lenders). Expanding the availability of credit (intelligently) expands opportunities. Expanding credit is a good in itself, and most governments look at expanding credit as a good thing. The Canadian economy has witnessed enormous expansions of credit as its become wealthier, and most of this is due to the smart decisions made by lenders (not borrowers - who are usually clamouring for more credit). In the American examples discussed in parts 1 and 2 of this series, it was not the lending to customers that went wrong, it was the borrowing activities. These risks are quite different.

Lenders will naturally retract their credit activities in the face of real risks - this is a system that is normally self-regulating in terms of risk because people who have money don't like to lose it to bad debt.

Regulatory attempts to reduce credit may not necessarily be to the advantage of customers, even if the public may perceive them as consumer protection moves. A more nuanced view on this might be more in the interests of consumers, and that nuanced view is distinguishing between borrowing from customers and lending to them, which have very different risk profiles for the public. It's the former that caused multi-billion dollar bankruptcies in the US. The latter hasn't seen any remarkable failures. And if they do fail: the losses are generally borne by well-financed backers, which is hardly a major priority for securities regulators (since these investors lose money all the time - that's the nature of high risk, high reward private investing). Who is in need of protection? The lenders? Are crypto asset trading platforms really better off by being barred from experimenting with extending credit to consumers in this relatively novel industry?

A Different Regulatory Approach

A different regulatory approach that could have been taken would be to expand borrowing in the crypto asset trading platform space, but overseen by securities regulators. If it's true that they have better expertise in this area than the companies that they regulate, they should surely be able to come up with rules that would have increased credit, and thereby offered customers more, not less. Or, if it's not true that they have special expertise, the dollar limits could simply be limited to amounts of money that aren't a huge issue for most Canadians. A few thousand dollars? A few hundred? Whatever the number is, even small-scale credit would enable these platforms to prove out the models and for regulators to see that credit can play a valuable role. Because credit is one of the few roles that a centralized, in-country platform can do much better than foreign platforms.

Foreign companies have a hard time enforcing debts, and they have a harder time accessing the customers. Canadian platforms could become leaders in this novel area, and do it in a way that doesn't put customers at risk. And to the extent there's some risk, it's worth considering that Ontario recently legalized sports gambling and people are routinely losing hundreds of dollars to online bets. Risk and reward are all around us, and governed by a wider variety of laws than securities law alone. Shares, beanie babies, stock options, old cars, gambling, insurance, cryptocurrency - to the public these are all risk-reward opportunities and maybe even entertainment. The sooner regulators take a broader look at how the public is engaging in risk, and where smart risks can be taken, the more rational the system will be in Ontario and the other provinces.

There is a missed opportunity to create a regulated sphere of activity for cryptocurrency trading platforms that gives them a leg up over the unregulated/purely on-chain competition, and gives consumers a greater reason to trade with Canadian platforms instead of offshore. The latter would help to prevent disasters like FTX (not domiciled in Canada) from affecting Canadians.

Credit has been an integral part of commerce for thousands of years, and is one of the marks of a dyanmic economy. It's possible to say no to one model for credit, and say yes to hundreds more. Credit is a nuanced subject, and simple bans may not lead to increased consumer welfare.