Credit is the lifeblood of economies. Since ancient times, borrowing has been subject to regulation. The image above is from section 48 of Hammurabi's Code, written 3700 years ago, and it concerns the delay of payment of debt due to crop failure. Debt and credit are two sides of the same coin, since a problem with the repayment of debt is a problem for the person who provided it. This has recently been a problem in the US banking sector, the cryptocurrency lending sector, and the subject of a number of recent Canadian legal changes.

This article discusses credit and debt in the context of cryptocurrency, with a particular focus on recent Canadian and American legal developments.

Credit In Crypto

There are a few different types of players in the cryptocurrency credit system, for example:

1. Companies that borrow from the public (many of which have gone bankrupt in recent years), e.g. BlockFi

2. Companies that lend to the public, e.g. Canada's Ledn

3. Banks that provide traditional credit to large companies that are active in cryptocurrency, but where the loan is not relevant to crypto

4. Companies that lend to other companies in the cryptocurrency space, e.g. Coinbase's emergency offer of $3 billion credit to Circle

5. Decentralized credit as part of algorithmic stablecoins, e.g. DAI

6. Decentralized credit through lending protocols, e.g. Aave

7. Trade credit from vendors, e.g. invoicing customers net 30

8. Quasi-decentralized borrowing systems for accredited investors

, e.g. Tinlake

The above systems are discussed below, but first a bit of background on laws about credit.

Modern Laws Of Credit And Debt

In modern Canada, it is more often the debtor who's cause is aided by law, since creditors are often considered to be able to fend for themselves more easily than debtors. Think payday loans, which are quite strongly regulated in Canada. The trend in recent years has been to restrict the provision of certain kinds of credit, while expanding others. For example, the Canadian government actively intervenes in the market for home mortgages to decrease the cost of borrowing, while attempting to reduce loans for other kinds of transactions (rather than global laws for all credit and debt). People in modern times have a complicated relationship with debt and credit.

Canada has a complicated legal system with regard to debt. There's federal banking regulation, provincial securities regulation, provincial financial institution laws, provincial consumer debt regulation (e.g. payday loans), special laws for home mortgage debt, government credit of various kinds set out in many laws, criminal regulation of interest federally, and then a various of administrative rules with respect to credit. There's also a wide variety of common law rules that have emerged from courts over the centuries. Canada has moved far beyond Hammurabi's Code.

A 2023 Snapshot of Debt In Canada

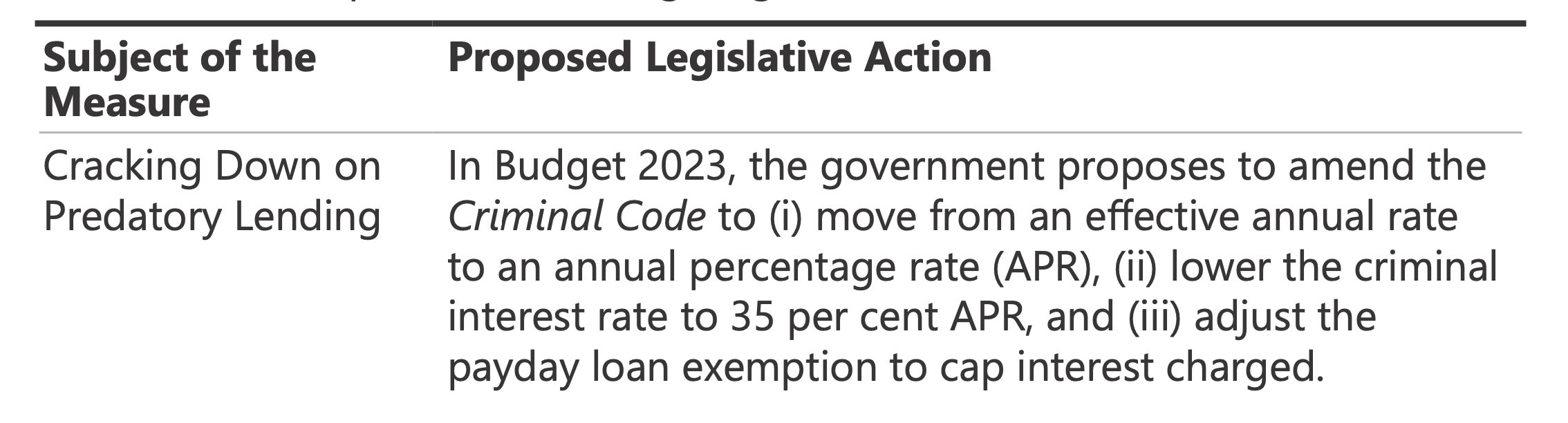

The 2023 federal budget proposes to reduce the rate of criminal interest (i.e. usury) from the current 60% per year to 35% (which matches the rate in Quebec but not the rest of Canada, where the Criminal Code rate of 60% prevails). The government describes this as predatory lending

, but the businesses that provide these kinds of loans are almost always lending to people who have a desperate need for money, but not the means available to pay (like wealthier people). The result of these sorts of restrictions is less debt offered to people who have limited means. That may sound like a win, but it's ignoring that these people have a strong need for money right now, and no one else is willing to provide that money.

Loans to marginalized people are not the norm in Canada. By far the largest sources of credit involve banks, mortgage lenders, the government itself, and other large institutions. Debt markets are worth trillions in Canada, with the federal government owing $1.15 trillion dollars to creditors. No agency properly tracks residential mortgages outstanding in Canada, but this likely exceeds $1.7 trillion dollars today (up from $500 billion 20 years ago).

Canada's debt market is huge, and expands every year. To some, this is a sign of an advanced, modern economy in which stability assures lenders that they can safely lend out their money. To others, this is a sign of people living beyond their means. The government's preferred number is the ratio of debt to total economic activity in Canada. Mortgage lenders look at the percentage of someone's income than is, or can go to, servicing their debt. Business lenders typically look at cash flow and other measures to decide whether or not to lend.

On-Chain Credit

What does Canada's debt situation have to do with cryptocurrency? For many people, cryptocurrency is the antithesis of the debt system that is considered the lifeblood of the economy. That's even a reason that economists have cited in criticizing cryptocurrency. The reason why cryptocurrency is the opposite of the debt system is that cryptocurrency transactions are irreversible and difficult to recovery legally, which makes it very difficult for a lender to assess and recover against in the case of non-payment. And yet, creative solutions have emerged.

The DAI System In Ethereum

There are a number of successful on-chain credit products, that work entirely (or almost entirely) in a decentralized manner: DAI is a great example. DAI works by having a user send their ether (ETH) to a smart contract that then issues a quantity of DAI (where each DAI is equal to $1 USD) that is significantly less than the value of the ether. In other words, the loan of DAI is over-collateralized

. An over-collateralized loan is quite rare outside of crypto, but essential in a world where someone could simply not pay back the loan (because they're anonymous and on the Internet). So, for example, a user deposits $100 of ether and receives $50 of DAI. Then, if the price of ether plummets, their DAI is liquidated. If the price of ether goes up, there's no effect. At a later date, the person with the DAI can return it to the smart contract and receive back the collateral they pledged, but with an interest rate charged according to the time that they had the DAI. This system produces two things that users want: a stablecoin (worth $1) that is not dependent on bank accounts (re: Silicon Valley Bank and USDC) and loans on-chain.

Why would someone want a loan of $50 in exchange for $100? One reason is that they believe that ether will increase in value, so they can take $100 of ether, get $50 of DAI, then purchase $50 of ether, resulting in a leveraged bet on the price of ether. This can be done entirely in the computer code of Ethereum and people have used it to create around $5 billion of over-collateralized DAI tokens.

Failures Of Lenders In The Crypto Space

The Canadian Securities Administrators (the association of provincial securities regulators) recently issued a staff notice that pointed out the failures of a number of lenders that were not on-chain systems like DAI. The staff notice mentions Voyager Digital (Canadian publicly-traded company that operated only in the US market), Celsius Network (American company), BlockFi (American company) and Genesis Global (American/offshore company). Voyager, Celsius, and BlockFi were all engaged in the business of borrowing from the public. Genesis was engaged in the B2B business of borrowing and lending. All of these companies have failed and/or been the subject of securities legal action by regulators in the United States. None of them were banks and users have suffered billions in losses due to their failures. What binds all of these companies together thematically is that they were receiving loans from the public.

The typical business model of lenders is to lend to the public, rather than borrowing from the public, and borrowing from the public is generally riskier for the public. The reason for this is that regular people are often not good at evaluating credit risk, and lack the professional understanding that lenders at banks and other traditional lenders have. Even payday lenders, which lend to the marginalized public, have a great understanding of the risks involved (because if they didn't, they would go bankrupt quickly and replaced with another lender with a better grasp on their clientele's ability to pay). Unfortunately, the failures of these companies is a great example of why borrowing from the public is a risky activity (for the public).

The Canadian Securities Administrators uses these recent failures as evidence that new investor protections

are warranted. And yet all of these platforms were actually not operating in Canada, and all of them were in a different market than cryptocurrency dealing (which is what the new rules are aimed at). This is probably just an opportunistic moment for regulators, rather than a real misunderstanding of what these companies were up to before the failed.

The new rules proposed by the CSA focus on lending to the public, rather than borrowing from the public. But lending to customers is a long-standing model for businessses, whereas borrowing from customers is not (in part because it's more heavily regulated - think banks). None of these failed businesses had much to do with cryptocurrency, since their business model was about borrowing from the public, not about crypto. In fact, their models would have worked even better with regular money, because they would have had a much wider potential customer base. But it also would have been more obvious that their activities are generally prohibited by laws against borrowing from the public.

Why Are Loans From The Public Treated More Seriously Than Loans To The Public?

There's an old joke that if you borrow $1000 from the bank that's your problem, but if you borrow a million dollars from the bank that's the bank's problem. When a loan is extended to the public, it is primarily at the risk of the lender. Lenders are often large companies, which can fend for themselves. Despite the talk by government of predatory lending

, the risk in lending to customers is primarmily borne by the lender, who may lose all of their money. The person who receives the loan has the money! They got what they wanted. But the lender may not get the money. When the public engages in lending to companies, they are the ones who might lose all of their money, and that's exactly what happened with the companies mentioned above. This difference in risk profile is why laws are generally concerned more with ensuring that the public doesn't engage in the business of lending out their money, as a consumer protection measure. There are people who view this as a problem for the public, because they should be able to engage in the profitable business of lending, but the failures of these companies show the obvious danger in permitting that. Governments throughout the world have typically enacted laws to restrict or eliminate this sort of business. Last year's settlement of the securities violation offences alleged against BlockFi (one of the failed companies) for $100 million dollars is a good illustration of what these laws are and how securities regulators enforce them. It's important to note that these laws are of general application and don't depend on the nature of what is being loaned, whether dollars, bitcoin, ether, or wheat.

Credit In Context

Despite regulators claiming great concern over cryptocurrency-related lending, the reality is that this is a tiny industry relative to overall credit. Canadian regulators cite the failures of the key borrow-from-the-public American businesses, but these failures are tiny relative to the recent failure of Silicon Valley Bank. Canadian crypto-related lending has likely never exceeded a billion dollars, in a market worth several trillion. Most of the platforms cited by the recent CSA staff notice were foreign companies that either never served Canadians, or barred them well before failure. Is this a serious concern? Probably not. That's not to downplay the magnitude of some Canadians losses (since some certainly used VPNs and other means to gain access to these platforms and the attractive rates they offered), but it seems cynical for securities regulators to discuss a foreign problem as if it's a domestic one. The failure of Silicon Valley Bank, an active lender to Canadian tech businesses (and registered foreign bank branch in Canada) may very well have a bigger impact.

What Is The Role Of Credit In Cryptocurrency?

To recap, credit is not native to crypto. But there are on-chain credit systems like DAI, though these are not at all like traditional loans because they require the user to place more than the value of the loan with the smart contract system (typically quite a bit more). Then there is the world of traditional borrowers and lenders, some of which migrated into the cryptocurrency world in the guise of new technology, but was in fact a medieval-era model of banking, much of which operated outside of the law (and then failed).

The role of credit crypto is relatively limited. In Canada, it's especially limited due to the recent staff notice warning platforms that buy and sell crypto to not engage in either lending to or borrowing from their users. Securities laws prevent many other kinds of credit to the public (i.e. people who are not rich, because people who are rich qualify as accredited investors

and are permitted to engage in loans that others aren't). Restrictions on loan interest rates also prevent at least some loans, and with the lowering of the maximum interest rate to 35% by way of the announced budget measures, this may become a larger factor. Undoubtedly, many people use access to traditional credit, like mortgages or home equity lines of credit, or even credit cards, to make purchases of cryptocurrency. No one knows how large a role that kind of borrowing plays in crypto.

Outside of national laws, new blockchain systems are being built to enable credit in ways that sidestep defaults by relying on collateral. This has its limits, as the most useful kinds of loans for businesses are certainly not the kind that require collateral, and most members of the public will not have much collateral. But perhaps that's a good outcome for the crypto space, because loans can create instability. But, overcollateralized loans through sytems like DAI are probably primarily used for speculation on prices, which can cause an increase in instability.

It's probably not laws or regulatory guidance that stops more lending involving cryptocurrency. It's the difficulty of recovering against the assets of the borrower - the same issue that ancient laws concerned themselves with. But considering that all of the on-chain lending systems (like DAI and Aave) have sprung up within the last ten years, it's likely that there will be future innovations in this space to help people gain access to more money than they have, at the price of paying money to those who have more of it. Whether in ancient Mesopatamia under Hammurabi or Canada under Justin Trudeau, the business of borrowing goes on.